Because gaming moves at the speed of light, it’s easy to gloss over or outright miss the quirky, bizarre or just plain interesting elements that go into the games we obsess over. Continue? will be where we dig back into the used bins and back-catalogue stacks to talk about the trends, personalities and uniqueness that powers the video game industry.

I recently deleted last year’s Watchmen downloadable games off of my PS3, which, of course, got me thinking about Zack Snyder’s movie. Seeing the most memorable moments of Watchmen–“Hurm.” “I did it thirty-five minutes ago.” “It’s all a joke.”– come to life was a reality millions of fans had long awaited. The movie adaptation of the classic graphic novel by Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons felt like it had a split personality: either slavishly devoted to the original work or implausibly diverging from it. It’s hard for me to say that I hated it, but that’s only because I realized the enormity of the task director Zack Snyder was attempting.

The game was even worse, though. Where I felt somewhat sympathetic to what Snyder tried to do in adapting the written work for the movie, the game just felt like the worst kind of cheap cash-in. Even after the bad taste of the Watchmen game dissipated, the nagging question I was left with was whether any Alan Moore’s work could be adapted to video game form. All his work boasts a wordy formalism–one that eschews the typical heroics of the superhero genre–readers get drawn into the inner landscapes of the characters and action seems perfunctory at best.

Moore’s superheroes generally don’t get bogged down in displays of world-shattering power or regularly scheduled fits of violence. That’s what felt so wrong about the Watchmen game. Both Nite Owl and Rohrschach were uncharacteristically chatty as they mowed down wave after wave of thugs, but their dialogue seemed explicitly designed to ping back to the graphic novel in exceedingly banal ways. By having the game be no more than level after level of repetitive bone-breaking, devoid of insight into the characters, Rohrschach and Nite Owl became the very kind of caricatures Moore was commenting on when he wrote Watchmen.

I’ve been recently re-reading Saga of the Swamp Thing, as it’s come out in new hardcovers, and it struck me how much action there was in Alan Moore’s debut on the American comics scene. The first collection circumscribes a complete character arc that would be great to place game players inside of. The character of Swamp Thing holds a complicated publishing history, but the version I’m most concerned with began as an atmospheric horror comic more than 20 years ago and focused on Alec Holland, the comic’s scientist lead character, who has transformed into a monstrous vegetable creature. Or so he thinks.

I’ve been recently re-reading Saga of the Swamp Thing, as it’s come out in new hardcovers, and it struck me how much action there was in Alan Moore’s debut on the American comics scene. The first collection circumscribes a complete character arc that would be great to place game players inside of. The character of Swamp Thing holds a complicated publishing history, but the version I’m most concerned with began as an atmospheric horror comic more than 20 years ago and focused on Alec Holland, the comic’s scientist lead character, who has transformed into a monstrous vegetable creature. Or so he thinks.

I think it’d be possible to make a good Swamp Thing video game by building on the virtues of what makes the work great, rather than in defiance of them like Watchmen: The End Is Near did.

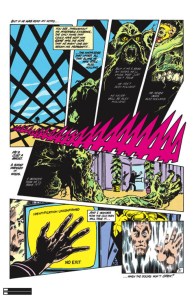

Of course, such an endeavor would have to be a horror game. That particular genre’s nothing new in video games but an ecological spin on scary gameplay might deliver a fresh and timely take on what gamers think of as frightening. In Swamp Thing, humans behave as monstrously as any demon or plant-man and there’s lots of philosophical food for thought in that dichotomy. Take a look at the first issue of Moore’s run and you’ll see what I mean. You’ll also notice that there’s a particular kind of rhythm in Saga of the Swamp Thing, too, achieved as much by different narrators as the lush, moody prose. It’s not just different characters describing the action, but different voices. Lots of the narration in Saga of the Swamp Thing happens in the second-person, but there’s also first- and third-person, too. It’s a unique decision to have narration that fuses in and out of the characters’ inner dialogues. One thing the Watchmen didn’t do was preserve the narrative texture of the original. Narration’s important because it not only sets the mood for the proceedings; it also gives you insight into the characters even as you’re reading, or playing, as the case may be.

The world of Swamp Thing spills over with fantastical elements that could foster strong gameplay ideas, too. Over the course of Moore’s work on Swamp Thing, the character learned that he was an Earth Elemental. This means he’s the embodiment of the latent consciousness of all of Earth’s flora. Some really interesting mechanics with regard to offense or traversal could be created out of a character who’s literally made up of his environment.

The world of Swamp Thing spills over with fantastical elements that could foster strong gameplay ideas, too. Over the course of Moore’s work on Swamp Thing, the character learned that he was an Earth Elemental. This means he’s the embodiment of the latent consciousness of all of Earth’s flora. Some really interesting mechanics with regard to offense or traversal could be created out of a character who’s literally made up of his environment.

The thing that really propels Swamp Thing as a comic is that it’s shot through with little epiphanies, so that when it’s taken as a whole, the whole endeavor feels expansive, not reductive. Once Swamp Thing learns that he’s not made up of the remains of Alec Holland, his consciousness slowly grows outward. A game that could replicate this feeling would wind up being regarded as so much more than the sum of its parts, even if some of those parts had previously appeared elsewhere in some other iteration. Games based on licensed properties can be smarter about what they pick and choose in the adaptation and, done right, they can do what Moore and his character did in Saga of the Swamp Thing. They can tap into something elemental.