The Prince of Persia concept has, at its core, a preoccupation with the passage of time. Even the graphic novel you did–which didn’t have any mystical time-travel or time-manipulation elements as seen in the games–was very much about the ripple effects of a character’s actions across the timestream. Do you think heroes need to be able to evolve over time to stay relevant, or are some heroes pegged to a particular moment?

Time does seem to be a recurring theme, doesn’t it? All the way back to the first game, when you had to rescue the princess before the sand in the hourglass ran out. I wish I could say I planned it that way, but honestly, it just seems to happen of its own accord.

The protagonists in most of the modern Prince of Persia games have been soulful but without being terribly angsty. The way I’ve always seen it is that their acrobatics tell us one thing about their personality and their dialogue tells us another. Was this a conscious decision?

Speaking about the 2003 game Sands of Time, because that’s the one I wrote, yes; I wanted to create a character who started out naive and not thinking too deeply about his actions, but was changed by the events of the story.

I really loved the first-person, after-the-fact voiceover in the Sands of Time game. I felt like it told us that he survived the things players were steering him through, but not how, and it told us about his personality as we were playing. Was this your preoccupation with storytelling cropping up or just an idea about narrative structure?

I was intrigued by the notion of creating a counterpoint between the onscreen action and the voice-over narration, in the style of old films noir like Double Indemnity and Sunset Boulevard, where the character narrating the story in the past tense is a changed person from the one we see onscreen, because he’s gone through this terrible experience. It creates suspense because it makes us wonder what’s going to happen that traumatized him so much. I don’t care for narration when it’s used to provide exposition or explain what you’re seeing; but when there’s a gap between the two, it can add another layer of atmosphere and meaning.

(More on Techland: An Oasis in Time: Techland Reviews Prince of Persia: The Forgotten Sands)

You used rotoscoping to get that fluid animation in your early games. Were you already thinking of film and video games as being kindred mediums?

You used rotoscoping to get that fluid animation in your early games. Were you already thinking of film and video games as being kindred mediums?

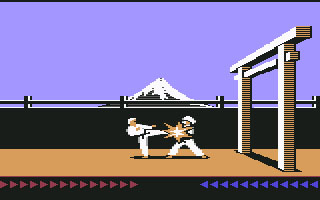

While I was making Karateka, I was taking college classes in film history. It seemed to me that video games were a new storytelling medium that was just emerging from the coin-op stage, as film had done 100 years earlier. So I looked to early silent films for techniques and inspiration.

It’s weird when you think about it: Karateka was wordless but–with all their dialogue–the characters in most modern action games don’t resonate the same way the ones in Karateka did. Would you keep a modern-day version of the game silent, or would you find another way to make the characters connect?

Funny you should ask. I have a strong idea about that. With regard to Karateka, I can only say, wait and see!