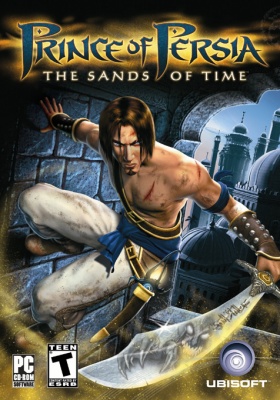

Video game movies tend to suck. That ain’t news. But the visual sizzle on display in he previews for Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time is giving movie-goers and gamers reason to hope. Dreamy-hunk–with-actual-acting-chops Jake Gyllenhaal ratchets up the anticipation meter, too. But, if the film translation of PoP winds actually being good, Jordan Mechner will be the reason why. Mechner created the acrobatic hero in the early days of PC gaming more than a decade ago. Not only is the Prince his character, but Mechner’s connection to the film medium run as deep as his video game roots. Mechner studied film in college and wrote the story for the upcoming movie, directed by Mike Newell. In the interview that follows, Mechner talks about how the Prince is different on the silver screen, and the differences in writing for comics, games and graphic novels.

How old were you when you started programming? What were your most impactful early video game memories?

I got my first Apple II computer when I was in high school. It changed my life. Instead of taking rolls of quarters down to the arcade, I could stay home and play games… and what was even more addictive, start programming my own games.

Let’s just step back for a second and let it soak in. Prince of Persia, a game concept that you created when you were twentysomething, is now a big-budget movie. What were your worst fears and highest hopes on the road to release?

I’ve been daydreaming about a Prince of Persia movie in one way or another for the past 25 years. And I’ve wanted to be a screenwriter for even longer than that. For this movie to have actually gotten made and released, on such a scale, with such an incredible cast and filmmakers, as my first screenwriting credit, is more than I dreamed.

A lot of people will be encountering the Prince of Persia for the first time in the movie. What do you think they need to know about your character? How does Dastan differ from the video game Prince?

We set out to make a movie that everyone can enjoy whether or not they’ve ever played a video game. It’s really an old-fashioned, romantic, swashbuckling adventure movie; there’s absolutely nothing special you need to know going in. That said, there are many elements of the movie that gamers who’ve played Prince of Persia will recognize and hopefully appreciate on an added level.

There have been other entities baby-sitting the Prince for some time now. What’s your level of involvement when new iterations of something based on Prince of Persia come out?

The versions I’ve been directly involved with, beyond the first two side-scrolling games, are the 2003 game The Sands of Time, the graphic novels, and the movie. I worked hard on those and feel a lot of creative ownership and investment. I wasn’t involved in the creation of the more recent games, the LEGO, toys, or other tie-in books. I’m delighted they exist, I root for the people that are making them, but I’m not a co-creator in any sense.

The Prince of Persia concept has, at its core, a preoccupation with the passage of time. Even the graphic novel you did–which didn’t have any mystical time-travel or time-manipulation elements as seen in the games–was very much about the ripple effects of a character’s actions across the timestream. Do you think heroes need to be able to evolve over time to stay relevant, or are some heroes pegged to a particular moment?

Time does seem to be a recurring theme, doesn’t it? All the way back to the first game, when you had to rescue the princess before the sand in the hourglass ran out. I wish I could say I planned it that way, but honestly, it just seems to happen of its own accord.

The protagonists in most of the modern Prince of Persia games have been soulful but without being terribly angsty. The way I’ve always seen it is that their acrobatics tell us one thing about their personality and their dialogue tells us another. Was this a conscious decision?

Speaking about the 2003 game Sands of Time, because that’s the one I wrote, yes; I wanted to create a character who started out naive and not thinking too deeply about his actions, but was changed by the events of the story.

I really loved the first-person, after-the-fact voiceover in the Sands of Time game. I felt like it told us that he survived the things players were steering him through, but not how, and it told us about his personality as we were playing. Was this your preoccupation with storytelling cropping up or just an idea about narrative structure?

I was intrigued by the notion of creating a counterpoint between the onscreen action and the voice-over narration, in the style of old films noir like Double Indemnity and Sunset Boulevard, where the character narrating the story in the past tense is a changed person from the one we see onscreen, because he’s gone through this terrible experience. It creates suspense because it makes us wonder what’s going to happen that traumatized him so much. I don’t care for narration when it’s used to provide exposition or explain what you’re seeing; but when there’s a gap between the two, it can add another layer of atmosphere and meaning.

(More on Techland: An Oasis in Time: Techland Reviews Prince of Persia: The Forgotten Sands)

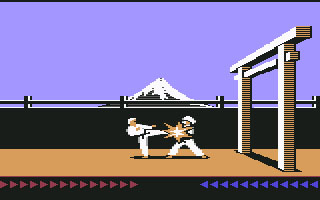

You used rotoscoping to get that fluid animation in your early games. Were you already thinking of film and video games as being kindred mediums?

You used rotoscoping to get that fluid animation in your early games. Were you already thinking of film and video games as being kindred mediums?

While I was making Karateka, I was taking college classes in film history. It seemed to me that video games were a new storytelling medium that was just emerging from the coin-op stage, as film had done 100 years earlier. So I looked to early silent films for techniques and inspiration.

It’s weird when you think about it: Karateka was wordless but–with all their dialogue–the characters in most modern action games don’t resonate the same way the ones in Karateka did. Would you keep a modern-day version of the game silent, or would you find another way to make the characters connect?

Funny you should ask. I have a strong idea about that. With regard to Karateka, I can only say, wait and see!

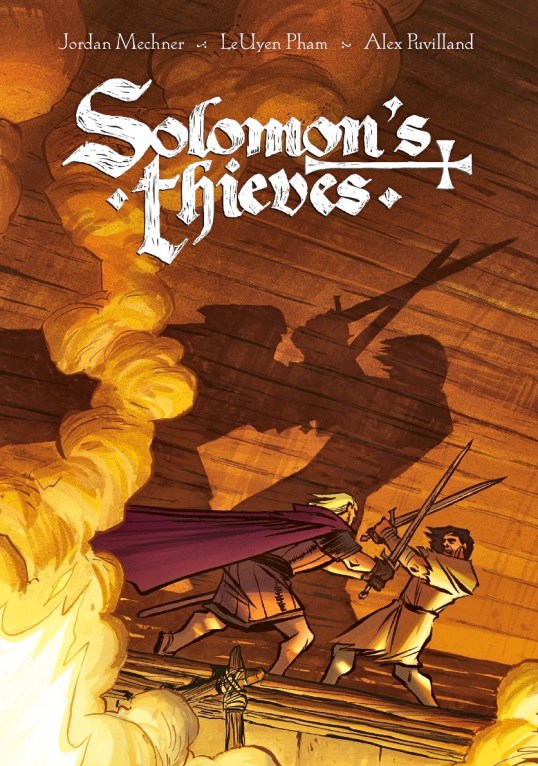

In your new graphic novel Solomon’s Thieves, you give the audience yet another reluctant hero in Martin. What do you think is compelling about protagonists who don’t know what to do with themselves?

In your new graphic novel Solomon’s Thieves, you give the audience yet another reluctant hero in Martin. What do you think is compelling about protagonists who don’t know what to do with themselves?

That’s reality, isn’t it? It doesn’t often happen in life that a benevolent authority tells you what you’re supposed to do with yourself, lays down the rules, you follow them and it all turns out great. At least I don’t know anyone whose life has been like that.

There’s opportunistic political maneuvering by the ruling classes in Solomon’s Thieves and the use of torture to pervert the judicial process. Were you intending for these elements to be commentary on the present-day or just reflect the time period the book happens in?

I was fascinated by the history of the Templar trial and it was important to me to tell that story truthfully and accurately. That said, I think part of the reason that history attracted me was because it resonates so deeply with our own time, and some of the things we’ve experienced in the twentieth century, that my parents grew up with and that we’re still experiencing today. Some things never change.

You’ve created extensively across three different mediums now. You made a documentary film and worked on screenplays for movies, as well as writing graphic novels and programming/directing games. What are the specific strengths of each medium or endeavor, in your mind?

Wow, there’s a lot to be said on that subject. A video game story is a story that’s written to be played, so the focus is on creating action that’s challenging and fun for the player. Movies are good at action too, and scope and spectacle, but the suspense and emotional impact comes out of our feeling of empathy with the characters and their plight. Whereas graphic novels engage the reader’s intellect and imagination in a more active way, they’re about the interplay between words and images, and the action doesn’t unfold in real time the way it does in a game or movie.

You’re also working on the screenplay for Michael Turner’s Fathom. Did you get to meet Turner before his unfortunate and untimely passing? Do you think there is a way to memorialize him in the film-making?

I wish I’d had the chance to meet Mike. I only know him through the stories I’ve heard from people who did know him. He was obviously an amazing human being and I know making a Fathom movie was a dream of his.

Aquatic action films have been hit or miss in Hollywood. What approach are you taking in adapting Fathom?

My approach was simply to try to make it as real and believable as possible, to ask questions and build it from the bottom up. If this race of underwater beings really existed, what would they be like? Given what we know about the oceans, physics, and evolutionary biology, how might their history and culture have developed over the past seventy thousand years, what kinds of things would they have and not have? And to try to put myself in this girl’s shoes, her emotional journey; what would it feel like to grow up being her? If I’m going to have any chance of making an audience believe this could happen, I need to believe it first myself.

What comics and games are you loving right now?

LEGO Indiana Jones. It’s the most brilliant movie tie-in videogame ever, I think. In comics, I’m enjoying the Dungeon series by Sfar and Trondheim.

You tend to focus on period pieces. Even your documentary Chavez Ravine focused on a Mexican-American community that disappeared in post-war Los Angeles. Do you enjoy looking back through history?

That’s one of the great perks of what I do — it gives me an excuse to spend time learning about other periods, cultures and places, and then have the fun of trying to bring that time and place to life in a new way. I love it.