In “Origins,” creators talk about their formative experiences with comics, movies, games and the things that influenced them to pursue lives of professional geekery.

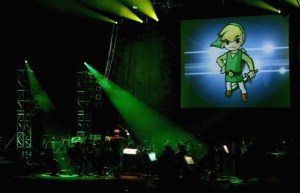

With all the sweaty madness and queuing that accompanies Nerd Prom each year, a concert with thousands of fellow nerds doesn’t sound like much of an oasis. But, Video Games Live is no ordinary arena show. The brainchild of game music composer Tommy Tallarico gives the orchestral treatment to tunes from old-school NES games like The Legend of Zelda and newer classics like Bioshock.

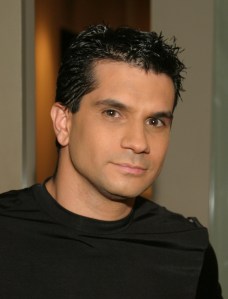

PBS recently announced that they’ll be airing a VGL special during the months of July and August, celebrating the phenomenon that the eight-year-old concert tour has become. Along the way, VGLs played Comic-Con for the last few years and this Saturday’s concert will include the world premiere of music from End of Nations, a buzzed-about MMO coming from Trion Worlds. Tallarico gave us a generous chunk of time to talk about getting his start in the games industry, why he started the successful Video Games Live tour and advice on breaking in.

I wanted to start off by saying congrats on the special.

Thank you.

Is this the first time that you guys are doing PBS?

Yeah, this is the very first time that we have been on PBS. Its pretty intense, pretty incredible when you think about, especially with all this “Are video games art?”crap going on, yknow, the whole Ebert thing. I challenge him to watch PBS–which has been the defining educational and cultural and artistic television station for over 40 years. I challenge him to watch the show and tell me its not art. Im throwing down the gauntlet, damn it!

Well, he has kind of recanted a little bit…

I have heard, yeah. I read something last week where he is like, oh, I should play games before I say comments like that. But thats cool.

Its not until he actually gets a controller in his hands that probably we will see the light, but that might be harder said than done.

Oh, I have always said too, and I was surprised that it came from — that kind of thought process was coming out of a guy like him who knows so much about film, because the reality is, we always compare ourselves with the film industry, but what I always found really interesting is, if you parallel the game industry to the film industry, there are many, many parallels.

When films first came out in the 1910s and the 1920s, they werent universally accepted by everyone. All the old people were saying, oh, what is this crap? These black-and-white flicking pictures, with no sound, no color? Vaudeville is where its at! That was all the old folks. Then it took a couple of generations of people who grew up on films, and then they got sound, and then they got color, and then they got better acting and storylines and things like that.

Now, take the video game industry. 1972, PONG comes out. What was it? Black-and-white, no color and no sound. That was kind of like our first film. Then we got sound, then we got color, and then we got story lines and acting and this and that. So again — and if you look at the timeline it wasnt really until the 40s and 50s, Gone With the Wind, Wizard of Oz, where these films really became mainstream, where films started to become mainstream. Look at that, about 40 years later after the inception of film.

Again, look at the video game industry. Here we are, about 40 years later, and now we are getting legitimatized and weve come such a long way. And our generation–Im 42 years old–I was the first generation that grew up on video games. Now that my generation is having kids, its evolving into our culture. It is becoming something that in 20 years from now, when my generation are grandparents, the cycle is complete. Then it wont be thought of as anything else except arts and entertainment. So it’s interesting when you parallel the two.

Yeah, it’s funny, because probably right now we are getting more video games with more depth than we ever have. They’re all kind of ambitious and have presentational aspects which you probably couldn’t even have technically done ten years ago, with the amount of graphics and sounds that all go into them.

So in terms of like your career, can we talk about your roots as a musician, and when exactly video games started to become a professional option for you?

Yeah. My whole life, my two greatest loves and passions growing up were video games and music. But I never thought to ever put the two together, because there was no such thing as a video game composer in the 70s. My parents were a product of the 50s. I was listening to Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley. In the early 70s, when I was four or five years old, I started playing piano when I was three, and I never — I just played by ear. I never had professional training or I don’t know how to read music. I have just always played by ear. So for me, I was four or five years old, banging out Great Balls of Fire and things like Jailhouse Rock to impress mom and dad. So that’s kind of how I got into it. Then my cousin is a famous rock star. So I was always kind of listening to his music as well growing up. Steven Tyler from Aerosmith, his real name is Steven Tallarico.

Wow. I don’t think I knew that!

So growing up, I naturally started to get into the rock stuff and Aerosmith and Van Halen and Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd. That led to picking up the guitar and things like that.

Going to the movies–Star Wars, especially–led me to orchestral sounds and classical music. Then I picked up Beethoven. When I heard Beethoven, again, I really listened to it. Growing up, we always hear stuff like in Bugs Bunny, in cartoons or TV commercials. But when I first sat down and really listened to it as music, that’s what really kind of changed my life. Hearing Beethoven was like, oh my gosh, this is what I want to do. I want to compose music. Again, I was at a somewhat early age. So I would just listen to the Beethovens and the Mozarts and Holst’s Planets and Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana. Then I started getting into more soundtracks by movie composers like Jerry Goldsmith and John Williams and those guys. But I never thought to ever put that together. It was always like, “Oh, I guess I want to be a film composer,” because that was the only outlet. I always loved video games, but, again, in the 70s and early 80s, composers weren’t doing that. There was no such thing. It was programmers doing blips and bloops.

The technological capabilities just weren’t there.

Right. This was before the digital music era. Then, when I turned 21, I left my parents literally crying on the doorstep, and I wanted to go out to California. I grew up in Massachusetts; I just got in my car and drove out West. I had no job, no friends, no money, no place to stay, nothing. I showed up in California, and I was homeless. I was actually sleeping under a pier at Huntington Beach for the first three weeks I was out there. But the very first day I got out there, I picked up a newspaper and I saw a job, selling keyboards at a Guitar Center. I went there the first day and they said, yeah, sure, you start tomorrow. The first day at work, I actually was wearing a video game t-shirt, which back in 1990, no one had video game t-shirt. Now you are walking in Wal-Mart and Target and freaking Hot Topic, and they are all over the place, right?

Right!

Back in 1990, no one had video game t-shirts, but I had one. It was actually a new shirt that I got for the new TurboGrafx-16, which just came out. The first person that walked in, the first customer I waited on, saw my shirt, and he was a producer at a video game company called Virgin, right down the street. One of Richard Branson’s companies. He was just starting it up. They asked me, he is like, “Well, you know about video games?” Oh yeah. And I downloaded 21 years of information on the poor guy. So he asked me if I wanted a job, and I was hired as the very first game tester for Virgin. And then I was — so I was in California three days and I was in the video game industry, and that was over 20 years ago.

That’s a hell of a level-up!

I was lucky. And I would literally bug the Vice President of the company everyday, I would say, hey, whenever you need music — if you need music for these things, let me know, I will learn how to do it. I will do it for free. And if you don’t like it, you don’t have to use it, at least give me a shot. And I would bug him everyday, and finally, the very first game that we were working on needed sound, and it was music. It was the original Prince of Persia. So I did sound for that and it won a bunch of awards and got great reviews.

This was the Broderbund release?

No, Virgin released a version of it.

Okay.

Yeah, it wasn’t the original. I think the original came out on what, the Amiga or was it the Commodore 64? Yeah, something like that, yeah. It was a version of that. So it was working with Jordan Mechner, but it was a version of it, and a different platform. So I believe the original came out in like 1989. Anyway, so won a bunch of awards, got great reviews for it, so they made me the music guy. He said, okay, well, you could do this then. That was pretty funny, and that was over 20 years ago.

So you have done — because this is only scoring games ever since?

Yeah, I am actually, crazily enough, in the Guinness Book of World Records as the person who has worked on the most video games. Not only for music, but on the most video games ever. The world record that I hold is for 272 commercially released games. But, I’ve since done like ten since then. So it’s like somewhere — closing in at 300.

Wow! That’s crazy. So clearly you have got the background in terms of the production side of making games, but what led to the idea to put on a tour?

My main goal for creating Video Games Live was wanting to prove to the world how culturally significant and artistic video games have become. I didn’t want to create a show for just gamers, for hardcore gamers or whatever. Look, guys like you and me, we know how awesome the music to Final Fantasy and Halo is. We know how great the cinematics for Warcraft are. I had the hardcore gamers in mind, but I also wanted to create a show that anyone can come to and have a greater appreciation of the game industry in general. Not just the music, but the visuals and the interactivity and the fun and the storylines and the characters, too. And that’s what Video Games Live is.

Did you worry about it seeming a bit lofty or high-minded to people?

It’s not just a high-society stuck-up snobby symphony on stage chalking out Super Mario Brothers in tuxedos. I didn’t want to have anything to do with that. And there are some other shows out there that do focus on more traditional and classical experience. And that’s cool! But I think one of the reasons why Video Games Live has been so successful over the years is because it’s something more than just a classical show. We don’t want it to be that. We do like 50-60 shows a year now, all over the world. I mean, no one has achieved kind of the level of what we are doing here. I kind of explain Video Games Live as having all of the power and emotion of a symphony orchestra, but combined with the energy and excitement of a rock concert, mixed together with all the cutting edge visuals, interactivity, technology, and fun that video games provide.

How have people who aren’t into video games reacted? Do they get that message?

Some of the greatest emails and letters well get after a performance are from the non-gamers. They come from the parents who brought the neighborhood kids or the grandparents who are bringing their grandkids to the symphony for the first time or whatever. They are the ones going, “Oh my gosh! I never knew that video games were this amazing. I never knew the music was so powerful and the characters and the storylines were so amazing. Now I get why my kids are so much into video games. And hey, these things look so great that me and my kids are getting together this weekend and they are going to show me some of the games they are playing.”

Sounds like a tent revival, dude…

And to get those kind of letters is really an amazing thing. That was the reason that I created Video Games Live. And to have the program now air nationally to 90 million people in the United States on PBS, the most well-respected television station in history, an artistic and educational and cultural institution, for the last 40 years… I mean, you think about it, right? When you turn on a PBS concert, it’s Sting, Andrea Boccelli, Paul McCartney, Elton John, Sarah Brightman, Enya, Yanni. The highest quality and worldwide loved performers ever, and now you are getting Video Games Live, too?! Holy s**t! It’s a great thing, not only for Video Games Live, but I really feel for the entire industry. And, maybe ten years from now, people will look back and say, “When did video games crossover into the mainstream?” Maybe this is one of the things that help it turn the corner, a national television special on PBS.

You rattled off a whole bunch of names, with some classical artists, but also modern contemporary pop artists. Who do you think are the game music composers that people should know about?

I think the name Koji Kondo comes to mind. He’s the composer of all the Mario and Zelda music. Now, when you think about it, 100 years from now, people will still be humming the Mario music. Just like 300 years later they are humming Beethoven, I am sure 100 years from now people will be humming Star Wars and know that music as well. But Mario will live on forever, and that music will as well. And when people think of Mario, that theme comes to your mind.

And there are so many fantastic composers today, too. A guy like Michael Giacchino, for example, who won the Academy Award this year for the movie Up. Well, Michael Giacchino’s been composing video game music for over 15 years. Now he is doing all the Pixar movies. He did ‘The Incredibles’ before that. His music is beautiful. Giacchino really, really sticks out to me as one of the top guys. And his roots are in the video game industry.

How do you make the older stuff in the VGL program sound good in symphonic arrangements?

The hard part, the challenging part, is already done for me. You ask any composer and he will tell you the same thing: coming up with that hook, that melody, is the toughest thing to do. And in regards to the stuff from classics like Castlevania, Mega Man, Metroid and all those, that’s already done. I mean, it’s all right there in front of you. Once you have that, creating arrangements or orchestrations or everything, that’s the easy part. So it isn’t really challenging to me. I have got the greatest job in the planet. I mean, it really is.

So, we talked a little bit about the long tradition of soundtrack albums for video games. Why do you think that hasn’t happened here, for American produced games?

Well, you know, I think it has, I really do. You just need to know where to go. There is a myth that video game albums sell in the millions over in Japan. It’s just that they make a lot more of their stuff available, like they do that with everything in pop culture. Whether it’s anime, manga, toys, characters, statuettes or whatever, they make more of it available. The Japanese have definitely welcomed it earlier and more often. I think that video games have — they are about maybe five to ten years ahead of us in regards to it evolving into the culture. But I think it’s all changing. I think we are in the midst of a change right now. I just read an article about Hideo Kojima talking about how Western developers are kicking Japanese developers’ asses?

Right, yeah. He has been talking about that for a little while now, for like the last couple of months.

Yeah, he was saying that he finds that people in the West are more motivated to succeed and do well, and that people in Japan aren’t as much. And he said he would rather work with Americans or work with the Westerners as opposed to Japanese. So I do think we are catching up. We are evolving to where Japan has. They have just done it quicker than us, but I think we are quickly catching up.

In terms of the set list and the way its evolved since you guys have been doing the tour, what is the process from the video game company end? Let’s say a Ubisoft or Microsoft or something. How do you work with them to get the music into concert?

Yeah, it’s a great question. First and foremost, the music has to be great. I don’t care if the game is a big seller or not. From there, once I figure out what the song is, I know pretty much most of the composers out there, so I will contact them. Then, we will kind of approach the publisher together. A lot of times, the publishers get a hold of us now.

When I’m creating a set list, I want it to be dynamic. I want a good representation of old-school plus the new stuff. High-energy impact stuff, with a massive choir and throwing in the kitchen sink, but also slow stuff and emotional and touching stuff. The show’s got some interactive fun segments in there, too, like bringing somebody up on stage to play Guitar Hero along with the symphony.

We also have other folks as well who play characters. We have a great talent called Flute Link, who dresses up as Link and plays the whole orchestral arrangement and flute arrangement of the music from Zelda. So, it’s always different. You know, I’ve created over 60 segments for Video Games Live. But we can only play about 18-20 of them a night. So, every single set list and every show is different. The show coming up at San Diego Comic-Con, for example, is 90% different than the set list we played a year before in San Diego, which was 80% different from the one we played the year before in San Diego.

And the great thing is games keep coming out and giving you fresh material.

There was a show at the Hollywood Bowl about five years ago that was the first time the Kingdom Hearts music had ever been played live.

Even with how popular those games have been in Japan?

Yeah, crazy, right? But again, it was 2005; it was somewhat of a newer game back then. And obviously things like Halo and Warcraft had never been performed live. Sonic the Hedgehog, never been performed live until we did it at the Hollywood Bowl. Everyone thought I was insane. But, now, the publishers contact us and say, “Hey, we got this new game we are working on, and the soundtrack is really great. Can you put it in the show?”

You mentioned that publishers get in touch with you once stuff is coming out. What have been recent standouts for you? Like where you have been playing a game and it has been like, okay, this works, I want this?

BioShock has some amazing sound and music. Assassins Creed II had some really fantastic stuff. We just put Uncharted 2 in the show, and that had some great stuff. But again, it doesn’t have to be a popular game. And Shadow of the Colossus, I am sure you have played that one.

Yeah, I have.

And again, financially, didn’t do so well. Was not a big commercial success, but the storyline and the characters and the interactivity and the score were all beautiful. So those are some of the ones that recently they have really stood out for me, and that we all have in the show now. Oh, the music to StarCraft II, which is coming out soon. We have been playing that music for two years.

That’s finally coming out next week, right?

Yeah. We have been playing Diablo III music for the last year-and-a-half. So we’re even playing games that aren’t even out yet.

So, as a last question: Let’s say a teenager, or a twentysomething kid goes to see a VGL show and decides, “I want to do that. I want to do what Tommy does. I want to do what Kondo-san does and make music for video games.” What’s the path there? What advice would you have for him or her?

It’s a great question. I formed a nonprofit organization about nine years ago called the Game Audio Network Guild. The letters spell out GANG. And the website for that is audiogang.org. Like I said, it’s a nonprofit organization. There are currently over 2,000 members who have signed up all over the world, representing 30 countries. It’s mostly professionals, but it’s people looking to get in the industry as well. It’s an organization that I founded because I wanted to spread information about–not only the creative aspects about what we do–but also the technical aspects and the business aspects as well. How do I get in the video game industry? What do I do? Where should I go? So joining GANG would be my first suggestion.

My second suggestion would be that the game industry is all about networking. Just putting together a demo CD or whatever and sending it to somebody in the mail? Don’t waste your time. Put together that demo, but meet the people face-to-face and put it in their hands. Have communication, like I did. Offer to do stuff for free, just for the opportunity to get your foot in the door.

So where are the best places to network?

Well, the Game Developers Conference is every year in San Francisco, in March. There’s The International Game Developers Association–another nonprofit organization–has groups all over the world. Meet the developers in your area, even if they are, say, smaller iPhone developers and get in with them now.

There are amazing books out there about game audio, too. Go on Amazon.com and type in “game audio” and you will get books like The Complete Guide to Game Audio by Aaron Marks. Alexander Brandon, who is the composer of the original Unreal series, has a fantastic book out there, Audio Processes. I forget the exact name of it. So, that would be my advice: networking, pick up the books, go to the events, and join GANG. And you should be well on your way. The hardest part of getting in industries like film and television is getting to the people who make the decisions, right?

Right. Definitely!

The good news is that, in our industry, that’s not the case. Getting to all those people is easy if you know what to do and where to go. If you are talented, you will get noticed and you will get work and you will be in this industry. By the way, that goes for everybody, not just musicians, but artists and programmers and producers and designers and marketing people and PR. If you show passion, that’s it. Passion and networking and talent, you will be in the video game industry.