Three years ago, Braid came out and changed people’s perceptions of what video games–especially independently developed ones–could be. The time-manipulating platformer gave players an experience that channeled the ephemeral nature of selective memory and the sting of lost love. Braid became a bona fide hit on the Xbox 360, thanks to a substantive maturity that ESRB labels don’t necessarily speak to. Its success validated both indie games and digital distribution on consoles in one fell swoop.

Jonathan Blow–the man behind the indie hit–has been keeping a relatively low profile for the last few years. He’s popped up at events like PAX and IndieCade to offer clandestine glimpses of his work-in-progress called The Witness. Visiting New York City this past week, the San Francisco developer pulled back the veil to let a select few play The Witness in its very early state. I had the chance to play the game and talk to Blow for a few hours last week. What I experienced had very little in common with Braid, but The Witness is very much a game that everyone should be looking out for.

(MORE: Happy Birthday, Samus! Nintendo’s ‘Metroid’ Turns 25)

Blow’s games require some deep thinking, and not just in terms of their play mechanics. Interacting with Braid did more than simply challenge players to figure out when to pause time on a particular level; it also made them think about decisions made throughout their own personal backstories and what they’d do differently if the chance were given.

In a similar way, The Witnesss is going to do for space what Braid did for time. The game focuses on an aspect of life–in this case, the very environments we move through–that we take for granted and forces you to look at it from a different angle. As I sat down in front of the laptop where Blow had the game’s build running, the first thing I noticed was the art style. Braid unfolded in impressionistic watercolors, but there’s more of a realistic approach to The Witness. Blow says, “it might feel a little bit hyper-real, but we’re not trying to be photorealistic.” I used an Xbox 360 controller to control movement in a first-person perspective, with a minimal control scheme. You never get a sense of what the protagonist looks like; rather, the focus is on what the player’s seeing.

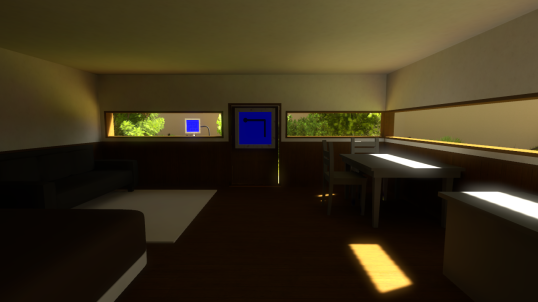

The game starts off in a dark room, with windows looking out on a tranquil suburban scene. The Witness is an open-world puzzle game at its core and it’s when you try to leave the room that you’ll encounter the first challenge. A glowing blue panel shows a line drawing with a large point and a smaller one at either end. Tapping A pulls the camera in tight and activates a pointer that lets you trace over the line. Mimicking the L-shaped pattern opens the door, and out you go into the unknown.

article continues on next page…

The puzzles get progressively more complex as you explore The Witness‘s gameworld and they’re all centered around specific themes. A grouping right after the beginning location features a three-way lock for the gate keeping you from the outside world. One puzzle panel’s in plain sight and easy to solve, which leads to a wire powering up to the next node you need to activate, done with a simple button press. Repeating the pattern leads to another button, but it’s inactive. Following the black, inactivated wires snaking through the environment reveals another, mostly hidden node behind a bush. Pulling a lever there activates another wire to that previous inactive node, which can now power up. Another line puzzle opens up the gate and out you go again into the larger unknown.

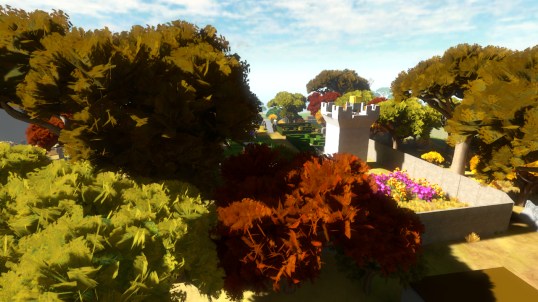

As you play, you find out you’re trapped on an island, supposedly by your own request, and the only way to make any sense of what’s going on is to roam around. Out in a small orchard, you come across a set of puzzle screens situated in front of a series of apple trees. One pattern, where a single line fans out into multiple forks, replicates itself at each station and you’re left to figure out what tracing path will solve the puzzle. It isn’t until you look around that you notice a single apple on a branch of each of the trees near the screens. The branching pattern of the trees roughly matches the one on the screen. A little bit of trial and error and you’re able to solve the puzzle. This made a tiny vibration of wonder work up my spine. How did I figure that out? It just kind of… happened.

However, that little bit of dawning gave way to my first bit of frustration with The Witness. I’ve doped out the scheme–find apple, draw a line to where it’d be on the forking diagram, proceed to next–but still couldn’t replicate the routine with consistency. A few things tripped me up: not being to find the apple on the next tree and then getting lost in the maze of forks when I did find the apple. It’s not like there’s a time limit or any such artificial stricture. It’s just me and the damn trees and the damned puzzle screens.

(MORE: Play ‘Saved by the Bell’ like an Old-School Nintendo Game)

Unbidden, that killer line from the Geto Boys’ hit song echoed in my mind, “Aw man, homey. My mind playin’ tricks on me…” Or was I playing tricks on my mind?

Stuck. What can I do, then? Blow assured me that the game hasn’t crashed all day and it’s been running smoothly, so I can’t assume that there’s a bug. He’s retired to the other room of the hotel suite we’re meeting in, and I yell weakly for him to come help. My heart’s not in the request, though. He didn’t hear me. Good. I don’t really want him to nanny me out of this cognitive cul-de-sac.

What did he say again? Oh, yeah… “It’s a work-in-progress for sure. Graphics are far from done. Everything is temp, really. Except the game design is far enough along that it’s a pretty good picture of what the game is going to be, except that… well, we’ll talk about that later.”

article continues on next page…

“Like, there’s going to be more of certain things. There’s going to be more story stuff basically. Yeah, why don’t we just talk about it after? So, the game has been very stable but this laptop has overheated twice. I’m just going to be hanging out in the other room working because I don’t like to peek over people’s shoulders while they play. So, yeah, just yell if something goes wrong.”

I think of all the other journalists and people who’ve played this game before me and how I’m probably doing worse than they did, stuck at a point they probably breezed through. I curse myself for not getting enough sleep, stressing over deadlines and the poor sleep habits I’ve had since my daughter was born. (Not that it’s her fault. She’s sleeping through the night now. It’s my fault. MINE.) I don’t have enough brain power for this.

(MORE: Gamer’s Death Linked to ‘Marathon Session on His Xbox’)

Yet, somehow, instinctively, I know that everything I need to solve this sequence is right there in front of me. I can tell by how the area I’m looking at is laid out. Maybe I missed something?

So, I walk back and forth around the surrounding area, tilting the camera this way and that and looking to see new things in things I already saw. Nothing. I meander along and find more of the audio recordings that are littered through the world. Unlike dozen of other games that feature this design element, they do almost nothing to illuminate what’s going on narratively.

One of them says in a male voice, “There’s no way you remember this, but you chose to come here of your own free will.” Great. Thanks for that. Should I even believe him? Another recording in a female voice quotes the 1971 writings of psychologist B.F Skinner. Something about man, the environment and responsibility for one’s actions. I don’t write down any notes because it’s pretty apparent the recording won’t do a damn thing to help me with those puzzles. (Later, when writing up this article, research reveals that he invented the “Skinner box,” an experimental environment where rats learn to obtain food by pushing a button.)

Eventually, I wander far enough that I find a new set of puzzles. These are further away from that first easy one, so they’re… harder? Whether that’s true or not, they’re definitely different. Another maze-like diagram. More start-and-end points. But these screens have little black dots in the pathways. Avoid them? No. Go over them? Yes. But I quickly learn that I can’t draw over my own line in a solving pattern. It’s a classic maze-solving rule but somehow I wasn’t expecting it. Each screen bears the same maze diagram but requires a different drawing to solve. Despite being stymied by the apples, this puzzle sequence clicks easier for me.

article continues on next page…

I do know how to solve things! Another run at the apple tree puzzles, then. And… nothing. Again. What am I missing?! More camera panning. Okay, there’s an apple I didn’t see before. Try the matching thing again. Great. That’s two down, on to the third. Apple spotted, but this time it isn’t quite clear what branch is the key one.

I draw a diagram, sure that it will help. It’s a crap diagram and it doesn’t help. Shocker. Ooh, let’s take a picture with a iDevice. (Hey, Blow, you left me alone and I feel dumb. Don’t judge me.) The picture on my iPod Touch helps but it’s not a breakthrough moment in and of itself. It takes more error stacked on more trial to finally get me through the apple tree puzzles. I exhale when they’re all done. There’s no reward, no happy music or charming cutscene. But, oddly, I feel like I don’t need those. The knowing–the process itself–is its own congratulations.

Taken all together, these areas illustrate the arc of engagement Blow hopes to create in The Witness. The first set with the security gate teaches you about drawing the line patterns, reading the environment for progression cues and how messing up cancels out previous solutions. The second set with the apples builds on those elements and introduces the idea that if you mess up the next link in a sequence, you’ll need to not only repeat the puzzle you’re working on, but the one before it as well. This mechanic isn’t ultra-cruel, as the solving pattern was still lit up, but I had to retrace it. Still, there’s room for error even in that and, believe me, I erred. Yes, I messed up things I’d already solved.

I play some more, taking in the odd dissonance of the gameworld’s architecture. Low, squat structures done in an odd, coldly minimalist style sit in the shadow of a weird windmill straight out of a fractured, alt-reality Holland. Who built this place? Why? For all my solving, the puzzles I’ve done aren’t giving me any answers to those questions. I walk into a building with sculpted cut-outs in its walls. Okay, these are easy. Well, now they are, anyway. Using the camera to line the cutouts with environmental elements on the outside reveals the tracing pattern. The Witness is an open-world game, which means that I could’ve found my way to these puzzles before the ones in the apple tree orchard. Would I have been able to figure these out, were that the case? The best I can come up with is a solid “maybe.”

article continues on next page…

It’s time to stop playing and process all of this. After I put down the controller, Blow gave me a flythrough of other parts of the island and showed me how the mechanics build on each other in increasing complexity. You’ll get different colored tracing lines, mirror image puzzles and still-water reflections of far-off formations that give clues as to what to do.

There seem to be some constants. Frustration, recursion, return to scanning the environment and finally solution: These are all part of the recipe for epiphany that Blow hopes players will take away from The Witness. It’s an ambitious goal: to codify in game design language the steps of understanding. It’ll be the same game and same puzzles for each player but the variability of the individual will yield unique experiences. The Witness literally showed me how my brain sees things and learns things.

Talking with Blow after the play session, I tell him that The Witness reminds me of the 1960s TV show The Prisoner, which subverted the tropes of the espionage action genre to become a cult hit. Patrick McGoohan’s classic kept viewers guessing and engaged at the same time. Blow says that the show was a slight influence but both his game and that show offer lots of interpretative freedom—but not a lot of guidance. He cites the iconic ’90s puzzle game Myst as a direct influence, with regard to the sense of mystery it drew players in with.

While The Witness left me with lots of questions, I do know one thing for sure about it: All the memory retention and pattern recognition exercise gestures are a deeper truth of how we move through the world and what we choose to see and not to see, especially with regard to how parts of our lives interconnect. Jonathan Blow is making a fable about perception; one that’s going to change how you look at video games all over again.

Evan Narcisse is a reporter at TIME. Find him on Twitter at @EvNarc or on Facebook at Facebook/Evan.Narcisse. You can also continue the discussion on TIME’s Facebook page and on Twitter at @TIME.