Sunday November 7th saw the 40th running of the New York City Marathon and thousands of runners journeyed through the city as fast as their feet could take them. One very special visitor to the city didn’t lace up a pair of New Balance but has nevertheless been running his own personal race for more than two decades.

2010 marks the 25th anniversary of Super Mario Bros., a game that ushered in a new wave of financial success and creative ferment for the home video game console business. Shigeru Miyamoto is that game’s lead creator and has worked at Nintendo since 1977. Miyamoto was initially hired as a staff artist, but he now holds the titles of Senior Managing Director and General Manager, Entertainment Analysis & Development Division.

In 1981, Miyamoto’s creativity delivered Donkey Kong, one of the biggest arcade games ever and the start of a legendary character’s lifeline. We’re not talking about the big, brash ape, though he’s a great character in his own right. No, it’s Donkey Kong‘s hapless hero–known as Jumpman at first–who’s arguably become the most successful persona the video game medium’s ever produced. Jumpman got the sobriquet “Mario” when the Donkey Kong game was exported westward and has since appeared in more than 200 games.

Miyamoto came to the US to celebrate Super Mario Bros.‘ 25th anniversary, and wowed fans with a surprise appearance at the Nintendo World store in Manhattan’s Rockerfeller Center. Gamers young and old hooped and hollered when Miyamoto took the stage and it’s easy to understand why. In person, Miyamoto evinces the same impish liveliness of his best work–like this year’s excellent Super Mario Galaxy 2–and a conversation with him also makes plain the thoughtfulness that sharpens the games he works on. I spoke with him two days before his Nintendo World appearance and the 57-year-old held forth on the influence of Rene Magritte on Super Mario Bros., taking the iconic series from 2D to 3D and the importance of simplicity in game design.

[vodpod id=Video.4780611&w=425&h=350&fv=vidVar%3Dhttp%3A%2F%2Fmedia.nintendo.com%2Fmario25%2F_ui%2Fflv%2Fmovie_history.flv%26amp%3BvidTitle%3DMario+25th]

The first thing I want to say is congratulations on the anniversary of Super Mario Bros.

Thank you very much.

Nintendo is a company that’s been around for a long, long time now, and many view you as an integral part of its longevity. Do you think of your own legacy and things you’ve done before when you are creating new games? Do you use them to inspire you?

I don’t really think of things in terms of legacy or where I stand in the history of Nintendo or anything like that. The important thing for us is to make sure that we’re having fun in our job.

So I really try to focus on, again, not only myself enjoying what I’m doing, but looking at my staff, and making sure that they’re having fun in their jobs as well.

(More on Techland: Super Mario Bros. Turns 25 Today)

Especially when you’re working on a series, there are times when you’re doing some repetitions, some work that maybe you’ve done before. You really want to make sure that the people working on it are approaching the project in a way that they’re not getting bored or frustrated, and that they’re thinking of new things and new twists and new appeals. That’s something we look at as well.

Your career with Nintendo actually started a little bit before with Donkey Kong, and we all know it became a big hit. But, when Donkey Kong became popular, why shift the focus to Mario? Why make him the focus of a new series of games? Why not a new character?

Well, the first reason is that Donkey Kong is just too darn big. And because he’s so big, we actually created Donkey Kong Junior to try to come up with the same sort of character, but in a smaller, more manageable size. And as we were looking at an 8-bit size, Mario became a much easier character to use.

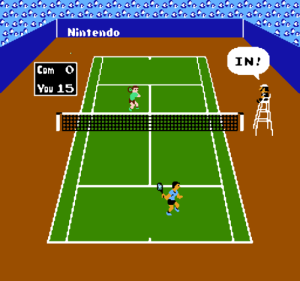

So that’s the first reason. My original goal was that I really wanted to use Mario in a lot of different games. So, for example, in the original Punch-Out! you’ll see Mario and Donkey Kong in the audience. You’ll see Mario is the referee in Tennis [a 1984 Nintendo Entertainment System game]. And then it became taking Mario and Luigi both and putting them in different situations in various games, and was the direction that I decided to take.

So that’s the first reason. My original goal was that I really wanted to use Mario in a lot of different games. So, for example, in the original Punch-Out! you’ll see Mario and Donkey Kong in the audience. You’ll see Mario is the referee in Tennis [a 1984 Nintendo Entertainment System game]. And then it became taking Mario and Luigi both and putting them in different situations in various games, and was the direction that I decided to take.

So, even from the beginning, you had envisioned Mario as a character you put in different settings, in different genres?

Exactly right. And it’s sort of common among the popular culture in Japan that a creator will take that same character and have him will appear in different manga. It’s also sort of like, maybe, Hitchcock appearing in all his movies. It’s sort of cool to have that character appearing here and there, whether or not they have a large role or not.

(More on Techland: It’s Me Mario and Friends Coming To An All-Star Party in North America)

But, Hitchcock appeared as Hitchcock. Do you see yourself as Mario?

[laughs] Yeah, I’m a little embarrassed but Mario is sort of my doppelgänger.

You started your career as an artist, not in programming but in drawing and designing. Do you think that’s informed your game design sensibilities in a particular way?

Yeah, I think, part of it has been very influential in that my industrial design background has allowed me to be able to take these concepts that I have in my head and be able to put them down on paper.

I have people on my teams do their own drawings and bring out the creation of their own ideas just to make sure that they’re true to what they have in their heads. So, in terms of thinking of design as building a structure into which we put in everything else, That’s the core for what we flow everything into. It hasn’t changed all that much.

That’s where you start, with a structure in mind, and then you fill it in with all these different concepts?

You’re right. And then you take that and look at how people will respond to this. And you try to make that structure into something that people will enjoy playing and being a part of.