Very few games have the kind of anticipation surrounding them that BioShock Infinite does. The first BioShock came out in 2007 and got hailed as a modern-day classic almost immediately for the way it wove character development, environmental design and philosophical underpinnings into a chilling and hypnotic experience.

BioShock Infinite is being built by the Irrational Games dev studio and takes the action skyward in an all-new politically charged setting at the turn of the century. (To find out more about BioShock Infinite, check out our report of the game’s unveiling and an interview with Irrational’s co-founder and creative director Ken Levine.)

One of the things that stoked the anticipation for Infinite even more was the amazing E3 demo staged at the annual video game trade show. That 14-minute glimpse just went public last night and makes for the deepest look yet at the airborne world of Columbia. I spoke to Ken Levine at E3 and he gave me some background on what exactly caused the floating city to disappear.

In the interview that follows, Levine talks about BioShock Infinite‘s main characters and how the game draws from politics and history, as well as the design challenges that Irrational’s trying to overcome with the ambitious new game. He proved, as always, to be smart, funny and passionate about what he and his team are building.

Read on for insight into one of 2012’s most anticipated games.

[vodpod id=Video.12629589&w=425&h=350&fv=%26rel%3D0%26border%3D0%26]

You’ve shown an all-new slice of Infinite at E3. About how far into the game was that sequence?

A third. The level may have some changes when we actually ship the game but that would be what happens to Booker and Elizabeth at that point in the game.

(MORE: Look, Up In the Sky!: First Video from Bioshock Infinite)

One of the things that struck me was that the play experience seemed very dynamic. It didn’t seem to be on rails there and looked like you can play that as you want. You can jump on the skylines to move around the level or you can hold your ground and let the enemies come to you. That kind of openness feels like a huge technological leap for you guys at Irrational, and not just technological, but design-wise, too. Can you talk about that?

We want you to inhabit Booker DeWitt but we want you to be you, too. Because the relationship we are trying to form is between Elizabeth and the player. But you’re playing through Booker. It creates an interesting design challenge. We want Booker to have an identity but we also want the player not to ever feel at odds about it again.

You are not going to do the battle scene where the player’s just wearing a fiction suit and going through a pre-ordained set of motions.

In BioShock 1, you were a cipher. But we tried to leverage the fact that you were a cipher in the storyline with what happens to you. We can’t do that again. We are not going to go back to just having you be a cipher. So, we started playing around with characterization and player agency.

You know I worked on a game called Thief a long time ago. I always enjoyed that Garrett could say, “Here’s what I’m going to do now.” Instead of somebody telling him in his ear what to do, he just said, “I’m going to go do this.” And there’s moments in the scenes where Booker goes, “Comstock house. Let’s go over there.”

But there also seems to be that one moment where Elizabeth was like OK, do we go there? This path? Or that path? Was that guided or was there choice there?

What we were trying to show is that Elizabeth can help you. That’s not a branching moment, like a choose-your-own-adventure. It’s more like “here’s part of the level” and “here’s another part of the level.” We’re just having Elizabeth point that out rather than a sign. In BioShock 1, we would’ve had signage that said that. Elizabeth, if you look at the demo, there’s a bunch of places where she’s just informational for you. And we want to do that without her making you feel like, “How do I clip it?” Like the paperclip from Windows, from Microsoft Office. You know, so, that was an important moment but it’s a subtle moment. But it’s an important moment because we’re just using the characters to inform the player of the possibilities.

Ok, so let’s talk about Elizabeth. It’s apparent from even that small sequence just how much work is being put into her. There seems like there’s a lot of things going on. There’s Stockholm Syndrome, and definitely some fear and naiveté. She’s like the ultimate sheltered child. What are the dangers that you’re coming across in fleshing out a character like that? If you can make her too naive and then she’s a cloying damsel in distress…

Well, one of the first things we did in the course of making the game was to figure she has that moment where she’s trying to be an angel. “Oh, the horse! We have to save the horse.” And then she sees what happens. And for me, when it comes to dealing with moral consequences, I never wanted Elizabeth going, “Booker, do the right thing.” Booker and Elizabeth go through this world together and they are both like, “What the fuck do we do here?”

You see shitty thing after shitty thing, and there’s even a moment when Booker stops the lynching, as you called it, he goes, “Hey, leave him alone, he’s just a postman.” Elizabeth kind of turns and goes like, “Oh, fuck. Here we go.” Because I don’t want a character to be judgmental of you. And I don’t want there to be clear right and wrong choices. I want them to be constantly scratching their heads. Because, look, BioShock games tend to be about unintended consequences. In all these choices you make, you are going to see unintended consequences. I didn’t ever want Elizabeth to be that voice of “do the right thing,” because that’s a pill, that’s not a person.

That scene’s really interesting because the Vox Populi reminded me almost immediately of Stalinism, and they reminded me of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, too. I had friends of mine, when he got elected, who were like, “This is going to change everything.” We’re finally going to have a Socialist government that uphold the highest ideals of that line of thinking, and then it kind of curdled into like yet another petty despot situation…

Another Animal Farm.

Right. Exactly. So, was that something you were drawing off of? Because that’s a cyclical kind of thing in history.

The actual inspiration for me, the thing that said, “Boom, this is what I want to do,” was when I was watching a documentary about a guy who was in the Baader-Meinhof. Are you familiar with the Baader-Meinhof?

Yeah-yeah-yeah.

And he was saying that he got into the Baader-Meinhof because, when it started in Germany in the ‘60s, they were pissed off that Nazis were in the government. Like, wait a minute, why the fuck are there Nazis in the government? He started there, and then a few years later, he goes, “I lived through this, this, and this, and one day I’m meeting with the PLO talking about blowing up an Israeli airline. Wait a minute, how the hell did I get from this to this?” And that to me is the path of the Vox Populi. They started off nobly.

But you become what you despise.

Exactly. You become what you despise because there’s this radicalizing effect. These groups start beating upon each other. They just keep pushing, and pushing, and pushing. And I really wanted to show that they both started off with good intentions. It was the same with Andrew Ryan in BioShock 1. Andrew Ryan grew up in Soviet Russia. His family’s business was taken away by the Bolsheviks. He forms Rapture as a place where no one can set limits on anyone else. Both he and the Vox Pouli started off by saying, “I want to do something different,” and they think they can control everything. If they just get this Utopia they want, everything will be fine. But then the pigs start sleeping in the bed…

Yes, the pigs are sleeping in the bed. So, here’s my question: You have these two factions; in the civil war raging through Columbia, you’ve got the Vox Populi and you have the Founders aligned with Comstock. Are we going to get the point-of-view of the common man? Or is that where Booker comes in?

The poor schmucks on the stairs are wealthy but they are probably not the most political people in the world and here they are getting ethnically cleansed from their neighborhood. But Booker and Elizabeth are the people in the middle. They are the most representative of ordinary people. What we’re trying to deliver is the feeling of the whole world being embroiled in this huge struggle, with Booker and Elizabeth having to stumble their way through that. I feel that way. Most of us feel that way.

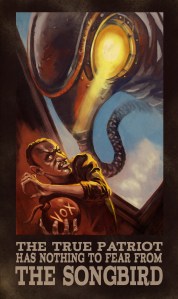

There’s that chilling part in the demo with Songbird. He’s obviously a hybrid creature of some sort. Is he all robot? Cyborg?

He’s something. [chuckles] The one thing I’ll say about him is clearly he’s connected to Elizabeth emotionally. He feels strongly about her leaving him. It’s not just his job.

When you guys announced in August of last year, you showed a bit of the Alpha, that steampunk cyborg-type enemy. Why wasn’t he/it in this demo?

You’ll see more. That thing we call an Alpha is a category of a kind of bad ass…The problem with demos is we can’t show how everything connects. We have choose foci and we didn’t want to have it overshadowed by a new Alpha in this demo because there’s already so much going on in what we’re showing.

You’ll see more. That thing we call an Alpha is a category of a kind of bad ass…The problem with demos is we can’t show how everything connects. We have choose foci and we didn’t want to have it overshadowed by a new Alpha in this demo because there’s already so much going on in what we’re showing.

Fair enough. Looking at Infinite in comparison to the first BioShock, it seems like there’s a bit of a recurring theme for you in terms of sketching out a moral breakdown of society. But with Rapture in BioShock, it seemed like more of a top-down decay. While the common man was a little bit complicit in it–by virtue of individual overreaching ambition and the genetic splicing–here it seems to be coming from both directions in society, from the top to from the bottom. You have the Vox, who are the proletariat and they decide to start a rebellion, and you have the Founders who are trying to suppress it. Am I over simplifying?

No. That’s about right.

We’re in a moment where one of the core currents in political discourse right now is populism and the dangers of populism. But what do you see as a counterpoint to that and how are you setting that up in the game?

There are certain sorts of populist movements on each end of the political spectrum. Often, both the left and right can adopt populist stances. The last demo [in August], you saw Saltonstall espousing the Founders’ politics and stumping about faith, flag, and family. Sort of a very populist right wing. Where here it’s all about Daisy Fitzroy, who’s the leader of the Vox Populi, and she’s basically talking how the big boss sees you as piece of cattle and he’ll turn you into chop. That’s what she says. And that was the philosophy of the Workers’ Movement, as we saw with the Industrial Workers of the World.

They said you have more in common with the worker in some other country than you do with a rich man in your own country. An internationalist movement, that’s what the Vox Populi is. And that’s a radical idea, the notion that nationalism is a tool to keep people down, and that’s obviously so at odds with the view of the Founders.

Who still cling to exceptionalist ideas.

Yes. And the nation is so important, the notions of faith, nation, and family, and you see that all over if you look through the bookshelves of recent political books. I remember that I wrote campaign posters for Saltonstall that said “For Faith. For Race. For Fatherland,” and then a famous politician had a book come out that was another version of the ‘Faith, Flag, and Family’ idea. That’s such a common thing through history…

Yeah. Like, these organizing ideas remain attractive and resilient.

Yep.

I just want to make sure I’m getting the timeline of the game’s history right. The 1900 World’s Fair happens. Columbia is unveiled and it’s awesome. Everyone’s like, “Oh my God.” It’s like a city on a hill. It’s a shining example of what America is capable of. Then they fire on the Boxer Rebellion.

Whoa, whoa. First, Comstock rises to power in the city. There’s a leader who gets pushed aside and Comstock comes in. You see a poster of him. He was made famous as the Hero of Wounded Knee like it says on the poster. He was already a nationally known figure in the game’s history.

And he’s a fictional composite here.

Yes, a fictional composite of a lot of different real people. And when he came into power, he moved the city in a certain direction. When he saw the Boxer Rebellion happening in this world he…

Decided to intervene.

He decided to intervene in a much larger way. Because we did intervene in the Boxer Rebellion. In the actual Boxer Rebellion, there was an international coalition that intervened because there were a bunch of missionaries and diplomats who were basically being executed. In the game, Columbia intervenes in a very violent way and they essentially secede from the Union because they think the Union is not American enough They disappear into the clouds and nobody knows where they are.

Was the Boxer Rebellion intervention the first of many?

I don’t want to give too many details away. But that was the big…

That was the flashpoint.

That was the flashpoint. Yeah.

So do the people of Columbia think of themselves as American still?

I think they think of themselves as more American than America. But they acknowledge that they are no longer part of the America. They say that exceptionalism is our heritage. We in Columbia deserve that heritage. America doesn’t deserve that heritage anymore because they are not living up to the true ideals.

Evan Narcisse is a reporter at TIME. Find him on Twitter at @EvNarc or on Facebook at Facebook/Evan.Narcisse. You can also continue the discussion on TIME’s Facebook page and on Twitter at @TIME.