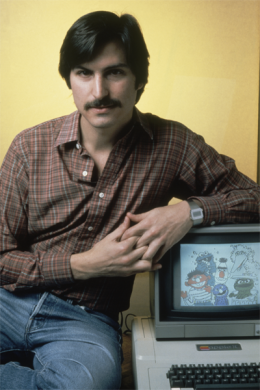

Steve Jobs and an Apple II in 1981

Thirty-five years ago, on April 16 and 17, 1977, more than twelve thousand proto-geeks flooded into San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium. They were there to attend a new event called the West Coast Computer Faire, and the room brimmed with excitement over a new, futuristic gizmo known as the “personal computer.” The throngs packed the aisles, marveling at microcomputers and related gizmos from tiny startups such as Cromemco, IMSAI, Northstar, Ohio Scientific and Parasitic Engineering.

One of the tiny startups benefited from having an especially slick booth located in prime real estate near the entrance. The company was called Apple Computer, and a handful of its employees, including founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, were demoing an unreleased machine they called the Apple II.

(MORE APPLE II CELEBRATION: I’ve helpfully suggested 14 ways to mark its anniversary, and rounded up some classic II-related photos from the 1970s and 1980s.)

The Faire’s attendees may have understood that they were in on the start of something big. At the time, however, there wasn’t any consensus that Apple and its computer were more significant than any number of other exhibitors among the 180 who filled the hall. Creative Computing‘s article on the conference didn’t get around to mentioning Apple until halfway through the third page; BYTE‘s report didn’t reference the company at all.

It didn’t take long until it was obvious that the Apple II was going to matter. The machine started shipping in the summer of 1977, and by the end of the year, it was gaining fame as was one of a trio of consumer-friendly, ready-to-use systems that were taking the personal computer beyond its hobbyist origins. The other two were Commodore’s PET 2001, which had also been displayed at the Faire, and Radio Shack’s TRS-80, which was announced in August.

The earliest microcomputers, such as MITS’ Altair 8800, were aimed at gearheads who knew how to wield a soldering gun; these new ones were plug-and-play, at least by the standards of the era. (Being willing to learn how to program your own computer in BASIC didn’t hurt.)

Corbis

Apple’s system has sometimes been called the first personal computer; it wasn’t, unless you use a definition designed to let it claim that honor. It may not even have been the best-selling machine in the early days. (The cheaper TRS-80, available at Radio Shack stores everywhere, challenged it on that front.) It was, however, easily the most visionary of the early personal computers — the one based on the clearest idea of what a PC should be, and where it could go. Given that Apple was barely over a year old and its only previous product was the unremarkable Apple I, it was an astonishing achievement.

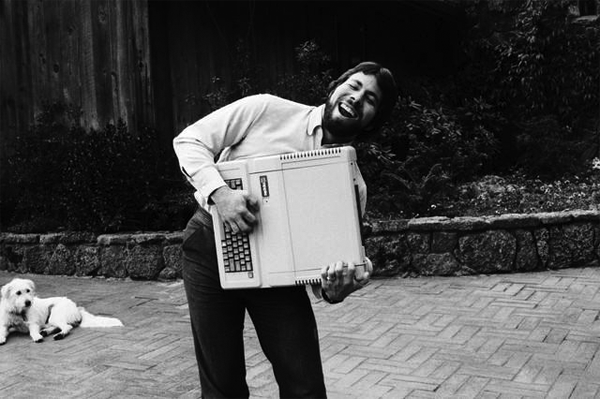

The vision that it displayed reflected the wildly different, complementary gifts of its two fathers, Jobs and Wozniak. Mike Markkula, the retired Intel millionaire who provided the money and business experience that turned Jobs and Woz’s garage outfit into an actual company, also deserves attention and praise. Without him, the II might never have made it out of the Homebrew Computer Club meeting where Woz demoed an unfinished prototype in December, 1976.

The insides of the Apple II weren’t purely Wozniak’s handiwork. (Rod Holt, for instance, was responsible for the super-efficient power supply.) But Woz came awfully close to designing it from scratch. He designed most of the circuitry, including ingenious technology for displaying color graphics and controlling the disk drive, and wrote the early software. And he did it for fun, not to make money. (He only quit his day job at HP when Markkula insisted that he devote full attention to Apple.)

Getty Images

Like many an Apple product to come, the II shipped with some notable holes in its initial lineup of features. For one thing, like many early PCs it displayed only upper-case characters. Worse: Woz’s version of BASIC could only handle integer numbers, making serious math impossible. Apple fixed that by licensing a more powerful BASIC from an Albuquerque, New Mexico company named Microsoft.

Yet the Apple II — again, like future Apple products — had the right features in place. It didn’t have what would later be known as a graphical user interface, but it did have a richer, more interactive feel than other PCs — it was one of the first models to do color graphics and sound right out of the box, and even came with two game paddles as standard equipment. In these respects, it had more in common with another product introduced in 1977, by a former employer of Steve Jobs — Atari’s VCS videogame console — than it did with other PCs. Such features made it a natural for games and educational software; they also made it an uncommonly inviting device, period.

The II’s case also had a pop-off lid which revealed eight expansion slots, making it far easier to customize the machine than you could most early consumer-oriented PCs. Dozens of add-in cards from third-party companies let you make the Apple II more useful by beefing up its memory, its graphics and its text capabilities and by adding peripherals such as modems, printers and floppy drives. The Apple II was so famously expandable, in fact, that Apple’s fans found it a shock to the system when the original Mac shipped in a sealed case with no official upgrade options at all.

The platform that Woz created was, indeed, a platform — the best and most successful container of its generation for interesting and useful hardware and software add-ons from third companies, much like the iPhone and iPad today. It’s no coincidence that VisiCalc, the first blockbuster PC application, was available only for the II at first.

So much for the Apple II’s insides. The outsides were also important, and that in itself was noteworthy. The earliest PCs, such as the Altair, looked like lab equipment. The PET resembled a desktop calculator that had gotten too big for its britches. The TRS-80 appeared to be designed by someone who regarded even a modicum of attractiveness as an unnecessary frippery. But the Apple II’s beige, rounded case, designed by Jerry Manock, looked great. It still looks great — it’s aged far better than certain more recent Apple products, such as the bulbous original iMac.

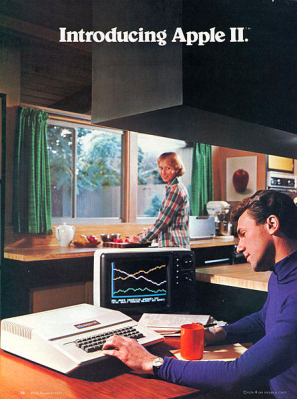

Wikipedia

The computer was marketed like a big-time product, too. Apple followed up on its surprisingly fancy Computer Faire booth with an unusually ambitious advertising campaign, created by Silicon Valley marketing guru Regis McKenna. (Not that it was hard to surpass the standards of the time: computer magazines were filled with ads composed of rub-on-lettering headlines, typewritten sales pitches and clip art.) Apple, unlike most of its competition, understood that there was a huge theoretical market for its products — if it could explain to normal people why they might want a computer in their home or business.

“Simplicity is the Ultimate Sophistication” read the headline on the first Apple II brochure. It’s a nugget of wisdom often attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci, but it also captured Apple’s philosophy, then as now.

Which brings up an intriguing question: what was Steve Jobs’ role in the Apple II’s creation?

Jobs, who was 22 at the time of the West Coast Computer Faire launch, had come a long way since the Apple I’s debut; back then, it didn’t even occur to him to put that computer inside a case until retailer Paul Terrell ordered fifty fully-assembled units. He clearly soaked up knowledge from Markkula and McKenna, who were 35 and 37, respectively, and grizzled veterans of Silicon Valley by comparison. But he was already Steve Jobs — demanding, unreasonable, essential. He “would pass judgment, which is his major talent,” said Chris Espinosa, Apple’s eighth hire (and still an Apple employee in 2012) as quoted by Steven Levy in Hackers.

It’s entirely possible that Woz, Markkula and others would have come up with a successful early computer without Jobs’ involvement; it’s tough, however, to imagine that it would have been as audaciously polished and consumery as the II.

Even in its most stripped-down form, the Apple II was pricey compared to the PET and TRS-80: it cost $1298 in 1977, or something close to $5000 in 2012 dollars. That was with a skimpy 4KB of memory and didn’t include the cost of a monitor. A truly well-equipped II, with a color monitor, 48KB of RAM and two drives cost several thousand dollars. By definition, therefore, it appealed to affluent types. As a user of Radio Shack’s proletarian TRS-80, I was already indulging in all the stereotypes about Apple fans being snobbish zombies that persist to this day.

Wikipedia

Still, the II sold extremely well — relatively speaking, of course. It took more than four years for sales to hit cumulative total of what Apple called “well over” 300,000 systems, or at least a bit over one-tenth as many units as 2012’s new iPad achieved in its first three days. Its various offshoots, including the Apple II Plus, IIe, IIc and IIGS, kept the platform viable into the 1990s, even though it began to feel like part of the industry’s past the moment that Apple announced the Macintosh in 1984.

Of course, the Apple II readied the world for the Mac, the iPod, the iPhone, the iPad and, come to think of it, every other major technology gadget of the past 35 years. More than any single other computing device, it’s the one that crawled out of the primordial ooze and scampered assertively in the right direction. Countless others followed its lead, and continue to do so.

Put it this way: if Apple’s only computer had been the Apple I, it would be remembered today only by scholars with an arcane interest in the prehistory of the personal computer. But if the company had folded after releasing the Apple II, it would still be one of the best-known PC companies of all time. The II was — and is — that important.

MORE: Diana Walker’s classic photos of Steve Jobs.