In 2013, there’s so much instant photography all around us that nobody bothers to call it “instant photography.” And it’s not just the photography that’s instant: At every public event of note, the audience includes people with smartphones who snap pictures and share them with the world, no wait required. It’s increasingly easy to forget that life was ever any different.

Back in 1960, though, instant photography was still remarkable, and still synonymous with Edwin Land‘s twelve-year-old invention, the Polaroid Land Camera. It was a pricey hobby — even the cheapest Polaroid cameras cost around $70, or more than $500 in current dollars — and considerably more cumbersome, complicated and glitch-prone than it would become in the 1970s, when Polaroid’s even more remarkable SX-70 camera came along. Instant-photography enthusiasts were far outnumbered by ordinary folk who used conventional film and couldn’t see what their snapshots looked like until they came back from the photofinisher days or weeks later.

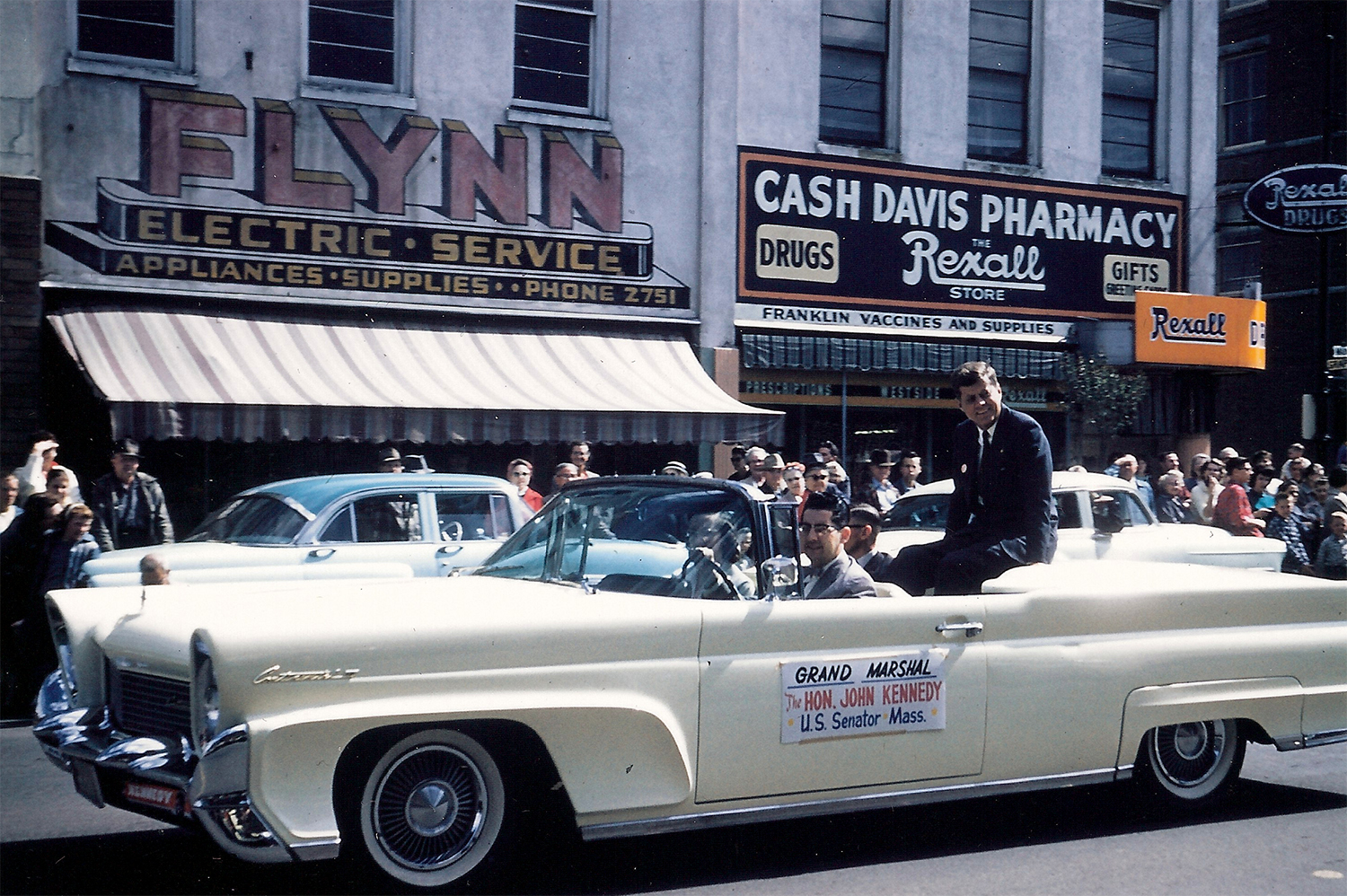

On April 23, 1960, a Land Camera owner attended the 1960 Pear Blossom Festival parade in Medford, Oregon. The Grand Marshal that year was Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, who was campaigning for the Democratic presidential nomination; our Polaroid photographer captured the senator’s visit in at least two instant pictures.

Five decades later, those two photos wound up in a case at an antique mall in Portland, on the other side of the state. In late December, as I antiqued during my holiday break, they caught my eye — and when I flipped them over and saw POLAROID stamped on their backsides, I had to have them. There they are at the top of this post.

The John F. Kennedy in these instant snapshots is the same confident, smiling, well-coiffed figure familiar from a thousand other pictures I’ve seen. (All in a historical context — I was born slightly over four months after his death.) But these aren’t prints or scans or reproductions of any sort. The photos themselves emerged from a camera which had been held a few feet from their subject, looking almost exactly as they do today; they document Kennedy’s visit to Medford, but they were also part of it.

Here’s a better look at one of the pictures, in which the senator is apparently posing for our anonymous photographer. I don’t know for sure where it was taken, but the most logical guess is that it’s the lobby of the Medford Hotel, which was the location of a post-parade luncheon. The pictures were taken with Polaroid’s amazingly speedy Type 47 film, introduced in 1959 and rated at 3000 ASA, which would have let our shutterbug take this interior shot without the use of a flash.

The partially-visible man at the far left, in necktie and belted trenchcoat, seems to be Pierre Salinger, JFK’s press secretary during both the 1960 campaign and his presidency, and later a European correspondent for ABC News. (I should have been able to figure that out on my own, but presidential historian David Pietrusza, author of 1960: LBJ vs. JFK vs. Nixon, identified him for me.) I’m not sure who the lady standing to Senator Kennedy’s left is.

And the bowtied gent in between Salinger and the lady — why, that’s Wally Watkins, the man who drove Kennedy in the Pear Blossom parade. Born in 1926, Watkins was a local businessman, involved at the time in real estate and timber. Almost fifty-three years later, he’s still a resident of the Medford area today. (Thanks to Paul Fattig of Southern Oregon’s Mail Tribune, who’s profiled Watkins in the past, for putting me in touch with him.)

Here’s Wally Watkins behind the wheel, driving JFK through downtown Medford.

Why did Watkins drive Kennedy’s car? Because it was his car — Watkins happened to own a beautiful cream-colored 1959 Lincoln Continental Mark III. “I had one of those convertibles where you could fold the top down in back so a guy could sit up on top back there,” he explained to me. A friend of his at the Pear Blossom parade thought it would be the ideal vehicle for the Grand Marshal and asked Watkins to play chauffeur. “I said ‘heck, yes, I’m a Democrat anyway,'” Watkins remembers.

Getty Images

A Polaroid 110A Pathfinder camera, manufactured from 1957-1960 and one of the models which may have been used by our Kennedy photographer.

April 23 also happened to be opening day for the fishing season; before the parade opportunity came up, Watkins had been planning to go fishing with his son at Oregon’s Klamath Lake. He admitted as much to JFK, who, he says, told him, “I’ll make it up to you, don’t worry.”

And indeed, Kennedy later sent Watkins a letter inviting him to his inauguration. “But I didn’t go,” Watkins laments. “I figured that he’d be elected twice, and I’d go to the next one.” It was not to be, but Watkins did get to meet Robert F. Kennedy, who campaigned in Medford eight years after his brother had — and only six weeks before his own assassination.

Back on April 23, 1960, Watkins didn’t know that the man in the back of his convertible would become one of the twentieth century’s most iconic figures, but it was still a big deal for a leading presidential candidate to visit Medford, a city with a population of 24,000. JFK made the visit as part of a two-day campaign trip to Oregon, which also included stops in Portland and Eugene at high schools, a Methodist church and a company called Ozark Industries. His itinerary indicates that he arrived in Medford at 9:30 in the morning and was gone by 3:30pm.

I’m glad that our Polaroid photographer recorded part of JFK’s time in Medford, but there are subtle signs that he or she may have been less than an expert Polaroid user. The Land Camera prints of the time were alarmingly fragile, prone to both damage and fading. The company addressed these basic flaws by bundling each roll of film with a tiny squeegee which the photographer was supposed to use — immediately — to swab down photos with a pungent protective chemical coating.

An excerpt from the manual for Polaroid’s Pathfinder 110A camera, explaining the crucial coating process.

In the case of these Kennedy Polaroids, this coating was done in a haphazard manner. You can see the result on the parade photo: The windshield of Watkins’ car is obscured by a streaky area, where uneven coating permitted the photo to age. Both pictures also have fingerprints along their edges, and the parade photo has an unexposed area along one edge which may stem from clumsy handling during the development process.

The intricacy of the Polaroid process may help explain why the bundle I bought at the Portland antique store contained only two snapshots. You couldn’t fire off a bunch of Polaroids in quick sequence, so it’s entirely possible that these two are the only ones our photographer got.

He or she (or someone else who came into possession of the snapshots) also chopped one border apiece off the pictures — an act which, as Christopher Bonanos, author of the excellent book Instant: The Story of Polaroid, pointed out to me, was probably done to squeeze them into a standard-sized frame or album.

But you know what? The fact that the photos are imperfect makes them more interesting. They’re one-of-a-kind defects — birthmarks which the pictures have carried for more than half a century.

As you’d expect, Watkins and Kennedy’s procession through Medford was captured in other photos. (Non-Polaroid ones, at least in the instances I tracked down.) Here’s a wonderfully evocative one by banker and photography enthusiast Shirrel Doty. I found it at the site of his son, storyteller Thomas Doty, and it was the first evidence I had that my Polaroids were taken during the 1960 Pear Blossom Festival. (At first, I thought they dated from a March 1959 Medford visit which Kennedy — not yet a declared candidate for the presidency — made to speak at a Roosevelt Memorial Dinner.)

Doty’s photo is the only one I’ve seen that shows the day’s events in color. Our Polaroid photographer didn’t even have that option: Polaroid didn’t release a color film until 1963.

The collection of the Southern Oregon Historical Society contains another photo.

Hubbard’s, a venerable Medford hardware store which the parade passed, has yet another picture of the Grand Marshal’s car, taken from the other side of the street, at its website.

In Doty’s photo, you can clearly see that the lady from my interior-shot Polaroid rode in the front passenger seat. Watkins doesn’t recall who she was, but says she was associated with the Democratic Party. Both the Doty and Historical Society photos also show a bespectacled man sitting alongside Kennedy: Watkins says that he was Bob Boyer, a local attorney and player in Democratic politics.

In my photo of the parade, Boyer is absent, and Kennedy is sitting on the back seat rather than perched on the back of the car. These two clues lead me to wonder if the photo was taken either before the parade began or after it ended.

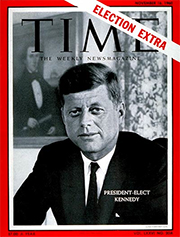

On May 20, 1960, Oregon held its primaries. John F. Kennedy won the Democratic one with 51 percent of the vote, a result which hadn’t always been a foregone conclusion. (He was running against Oregon Senator Wayne Morse, a favorite-son candidate who dropped out of the race shortly after receiving only 31 percent of the primary vote in his own state.) But when Kennedy won the presidency on November 8, Oregon went for Richard M. Nixon.

And that’s the end of the story — except for a grim postscript.

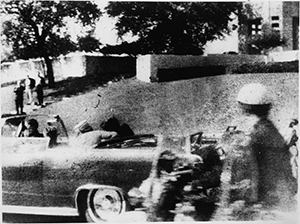

It’s impossible to look at a photograph of John F. Kennedy riding in an open car without thinking about his Dallas motorcade on November 22, 1963. When Kennedy rode into Dealey Plaza, he was sitting, once again, in the back seat of a Lincoln Continental convertible. This example was manufactured two model years after Wally Watkins’ Mark III, and had been heavily customized for presidential use.

After the assassination, that particular Lincoln was modified further, returned to service and used by four other presidents until 1977, when it was retired. Today it’s on exhibition at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

(I find the notion that other presidents continued to ride in the car deeply eerie, but maybe that’s just me; I also have trouble dealing with the fact that we still put on events at Ford’s Theatre, sometimes with the current president of the United States in attendance.)

As Kennedy’s motorcade cruised through Dealey Plaza, a 31-year-old Dallas resident named Mary Ann Moorman was there with her Polaroid 80A Highlander camera. She’s visible in the Zapruder film, standing along the edge of the grassy knoll with her friend Jean Hill, Highlander in hand.

Moorman snapped a photo approximately one-sixth of a second after a bullet struck the president. You can see Jacqueline Kennedy, in her Chanel suit and pillbox hat, turning towards her husband, who seems to be slumping. Other than that, it’s not clear what’s going on. The general murkiness may help explain why the photo is beloved by conspiracy theorists, some of whom believe that it shows a second gunman who’s been nicknamed “badge man.”

Moorman’s sad little piece of history is the famous JFK Polaroid, the one which I’ve vaguely known about for years. But from now on, when I think of John F. Kennedy and Polaroid, I’ll think first of a 1960 trip to Medford rather than a 1963 one to Dallas — and I won’t feel quite so melancholy.