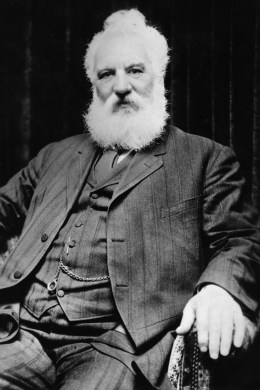

Scottish inventor Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922) who invented the telephone.

Alexander Graham Bell, as you probably know, invented the telephone. What you may not know, is that he also made crucial refinements to the first techniques used to record and play back sound. And yet contemporary listeners have never been able to hear Bell’s voice — until now, thanks to researchers at at the Smithsonian, Library of Congress and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

The first recording device — Thomas Edison’s phonograph — used tinfoil-covered cylinders to encode sound waves. Bell (Edison’s rival) and his associates came up with the more commercially viable idea of coating cardboard tubes or discs with wax to do the job. But wax recordings were incredibly fragile, capable of only limited playback and prone to deterioration over time.

So when researchers at the Smithsonian discovered a piece of paper in a collection of the earliest audio recordings ever made that transcribed an 1885 recording ostensibly made by Bell, then matched that to an actual wax-on-cardboard disc sporting the initials “AGB” and the same date, April 15, 1885, they couldn’t just drop it into an old-school player and crank away. How to validate the awesome possibility that they’d discovered an actual recording of one of America’s most famous inventors?

According to Bell biographer Charlotte Gray:

Bell conducted his sound experiments between 1880 and 1886, collaborating with his cousin Chichester Bell and technician Charles Sumner Tainter. They worked at Bell’s Volta Laboratory, at 1221 Connecticut Avenue in Washington, originally established inside what had been a stable. In 1877, his great rival, Thomas Edison, had recorded sound on embossed foil; Bell was eager to improve the process. Some of Bell’s research on light and sound during this period anticipated fiber-optic communications.

Inside the lab, Bell and his associates bent over their pioneering audio apparatus, testing the potential of a variety of materials, including metal, wax, glass, paper, plaster, foil and cardboard, for recording sound, and then listening to what they had embedded on discs or cylinders. However, the precise methods they employed in early efforts to play back their recordings are lost to history.

As a result, says curator Carlene Stephens of the National Museum of American History, the discs, ranging from 4 to 14 inches in diameter, remained “mute artifacts.” She began to wonder, she adds, “if we would ever know what was on them.”

Stephens then learned of a possible solution to her problem via the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which had developed technology capable of extracting computer audio from legacy mediums using optical scans. Working through the Volta Lab collection, the Smithsonian eventually discovered and submitted the 128-year-old wax disc believed to contain Bell’s voice to the Library of Congress. The LoC then used Berkeley’s technology to scan and create a digital map of the disc’s surface — all without disturbing the disc itself. The recording’s contents were checked against the transcript on June 20, 2012, allowing the Library to positively identify the voice as Bell’s.

You can hear the definitive, awe-inspiring moment in the audio selection below, as Bell identifies himself for posterity at the end of the recording, speaking to us from the 19th century: “Hear my voice — Alexander Graham Bell.”

The complete recording, which includes Bell reciting numbers and other phrases, is available here (including a scan of Bell’s handwritten transcript).