A study suggesting Facebook will lose 80% of its peak user base by 2017 is whipping around the Internet this week, but there’s a problem: It’s just not going to happen.

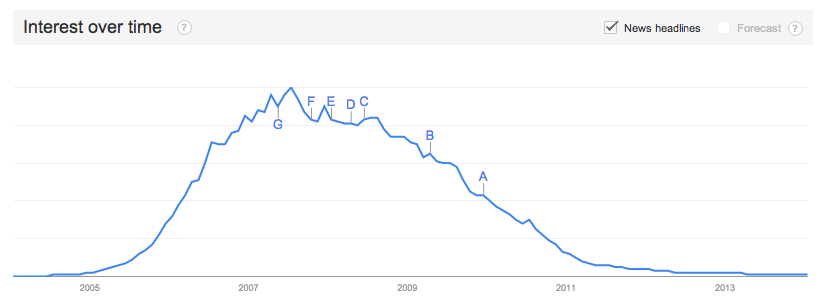

The study (on which TIME previously reported) attempts to apply an infectious disease model to the phenomenon of social media network abandonment. The researchers—two Princeton students—looked at online search queries for “MySpace” over time and noted the significant drop-off as users left that platform, as seen here:

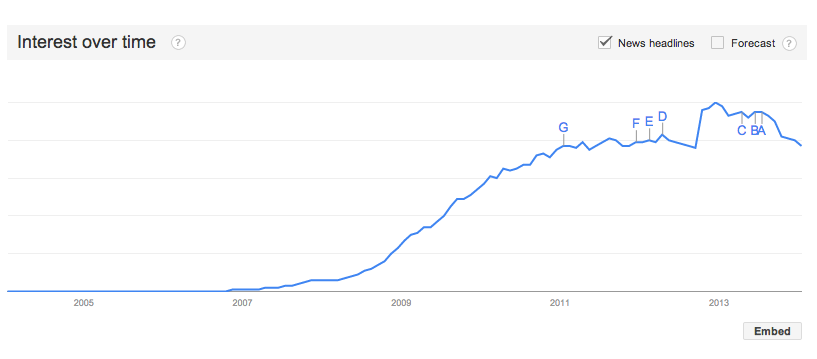

The study then applied the same model to searches for “Facebook.” Facebook, the study finds, is “just beginning to show the onset of an abandonment phase. Extrapolating the best fit model into the future predicts a rapid decline in Facebook activity in the next few years.” Here’s search interest in Facebook over time:

Here’s problem number one: If we allow for a moment the idea that search interest is a viable measure of a social network’s popularity, then yes, interest in Facebook is, admittedly, showing a very slight dip. But Facebook is absolutely killing it in direct comparison to MySpace. Check out search interest for the two side-by-side—MySpace in red, Facebook in blue:

But here’s the thing, search interest has nothing to do with a modern social network’s future prospects. We search differently than we used to. More Internet users may have learned to type “Facebook.com” into their browser window instead of doing a Google search for “Facebook” and accessing the platform that way. About half of Facebook’s daily users are mobile-only, using apps to access the service instead of their desktop browsers—so those Search-“Facebook”-to-Access-Facebook searches are probably decreasing because of this, too. Finally, Facebook hasn’t made major news recently, so there hasn’t been a good reason to Google “Facebook”—but that’ll change next week immediately after its scheduled earnings call.

Alexander Howard, a fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at the Columbia Journalism School, told TIME via Facebook messages that “applying models from the biological world to social networks and the broader online world isn’t an unreasonable approach to studying the dynamics of what’s happening there and why.” However, he brought up another reason this study is a miss: Facebook has the critical mass crucial to keeping a social network thriving.

“Where this parallel falls a bit short is in its predictive value for abandonment,” wrote Howard. “As long as a preponderance of friends, family, colleagues are on Facebook and using it—and are not somewhere else—and there is a social or even professional expectation to be on Facebook, there is significant friction against leaving it, particularly given network effects. If Facebook becomes an even more significant supplier for identity credentials and application logins, there will be even more gravity holding people here.”

Basically, you won’t leave Facebook because all of your friends and family are on Facebook now. There’s little reward for being the first of your friends to go somewhere else, as there’s no guarantee anybody will follow you there. MySpace never achieved this critical mass (your grandma never had a profile there—probably) so when Facebook started surging, there was no penalty for MySpace users to switch over. (Facebook’s original college-student-only rule also gave it a more “grown-up” feel than MySpace, helping to pull the first generation of MySpace users away just as they graduated high school.)

On top of that, Facebook is by now a much more complex ecosystem than MySpace ever was, with strong bonds to publishers, advertisers and other services across the Internet. Facebook’s code is all over the web, even on this very page, giving it heft that’ll help it endure and thrive on the constantly evolving Web. Facebook has also had a long pattern of year-over-year growth, now boasting more than 1.19 billon monthly active users per its last earnings report. 800 million of those users just aren’t about to get up and go in three years’ time.

A Facebook spokesperson told TIME the report is “utter nonsense.”

For what it’s worth, the study’s authors acknowledged their work hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed—a key phase of any scientific research. One author, Princeton graduate student Joshua Spechler, told TIME via e-mail that “The manuscript posted on the ArXiv is a preprint, which we have submitted to a peer-reviewed journal.” Spechler declined to comment further “until the completion of the peer review process.” It’s not clear how their work got traction across the web before this critical research phase. One guess: people were sharing it on Facebook.