Dropbox CEO Drew Houston introduces the Dropbox Platform at the company's DBX conference in San Francisco on July 9, 2013

At cloud-storage company Dropbox‘s DBX event today in San Francisco — the first developer conference the company has ever held — CEO and cofounder Drew Houston began his keynote by announcing that the service now has 175 million users. And then, as he started to talk about product-related news, he began with the sort of audacious declaration that’s entirely standard in tech-company keynotes: “Today, the hard drive goes away.”

In this case, however, I wasn’t sure whether Houston’s statement was too audacious, or not audacious enough. For an awful lot of people, Dropbox is already the great hard disk in the sky — a single place to store documents, photos, videos and other items where they’re available from everywhere and can reliably sync themselves onto devices of all sorts. (Users get 2GB of space to start and can get more by paying or through referrals.)

Did Dropbox have any announcements on tap that might turn it into any more of a hard-drive killer than it already was?

Turns out that it did. Houston and several guests spent most of the keynote talking about the Dropbox Platform, a suite of technologies which lets apps of all sorts treat Dropbox storage even more like a hard drive — and allows them to manage data of all sorts, not just the stuff we think of as files stored on a disk.

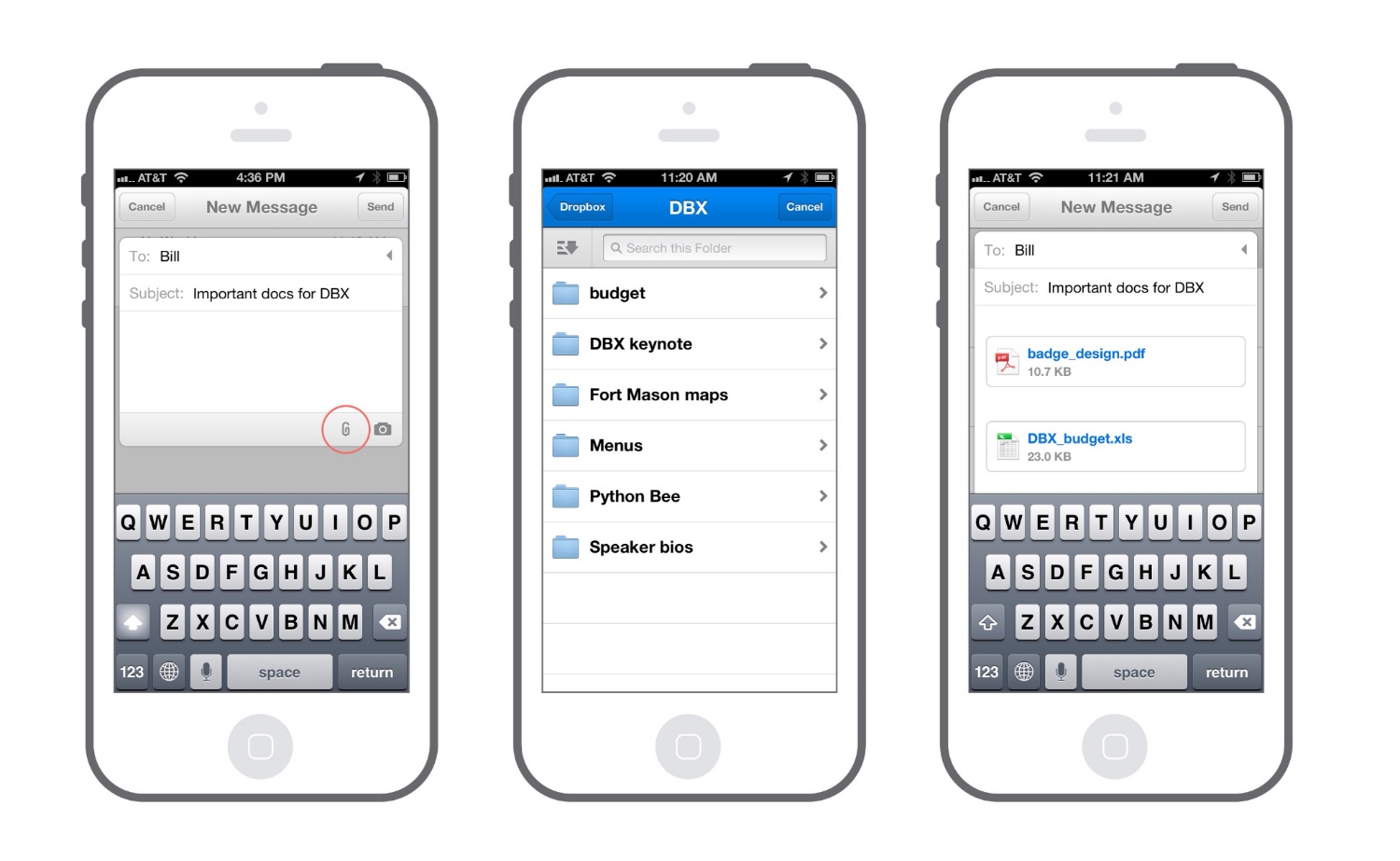

By using just a few lines of code, developers of iOS, Android and web apps can now plug in Dropbox’s standardized file Chooser and Saver, letting users open and save files stored on their Dropbox accounts as if they resided locally. More significantly, developers can now use a new Dropbox feature called the Datastore API to store and sync anything: settings, to-do items, game high scores, passwords or any other piece of information an app needs to preserve and retrieve on an ongoing basis, especially across multiple devices.

Lots of apps store and sync data already, often using home-grown techniques. But Dropbox is betting that developers will choose to skip the ugly work involved in doing this themselves in favor of handing off the job to Dropbox. If they do, it could make the service even more essential to modern net-enabled, highly mobile computing than it already is.

After the keynote, I met up with Houston and asked him whether Dropbox, which was founded in 2007, always intended to go beyond files and folders to become a universal repository for anything made up of bits and bytes.

“It goes back to the pretty early days,” he told me. “A lot of the inspiration was, ‘How do we make all of these things work together?’ The files were the most important stuff first, but in the future you’ll have this completely seamless experience.”

Dropbox has been so successful so far not because it was the first online hard drive — it wasn’t, by a long shot — but because it makes storing files online into a simple, reliable and therefore addictive process. How much harder will it be to preserve those essential virtues now that Dropbox is handling individual items of all kinds, not just entire files? Houston says that it’s no cakewalk. “We’re kind of gluttons for punishment on this stuff. We love these sorts of problems. That’s what makes it exciting.”

With the Datastore API, Dropbox isn’t competing against its traditional rivals — other cloud-drive services such as SugarSync, Google Drive and Microsoft’s SkyDrive — so much as against operating systems themselves. It’s doing things in the same ballpark as capabilities that Google is building into Android and Apple (through iCloud) is building into iOS. Yet it’s doing those things as a third party, which means that there’s a limit to how deeply it can dig into the operating systems it supports.

It’s a daunting challenge — so much so that it might feel hopelessly unrealistic if some brand-new startup were undertaking it. With Dropbox, whose existing features are already supported by more than 100,000 apps, it merely seems extremely ambitious. If the company can convince a critical mass of app developers to build in comprehensive Dropbox support — among the apps and services doing demos at DBX are Yahoo Mail, 1Password and PicMonkey — it might not matter all that much that it isn’t part of the operating system itself.

“We’ve been here before,” Houston says. “That’s why we go to the developers. They know we’re going to support them on whatever platform they’re on.”

I asked Houston whether there was such a thing as a developer who’d rather maintain complete control over its data-wrangling rather than hand off responsibility to even a service as popular and well established as Dropbox. “Our goal,” he told me, “is to make it just the obvious choice. We’re not forcing anyone to use this, we’re just making it available. [Developers] don’t have to sweat the details, because we’ve done the hard work.”

Of course, Dropbox has to do more than just convince developers that storing just about anything and everything in Dropbox is a good idea. It also has to sell the proposition to consumers and businesses, including both existing users and ones who aren’t yet aboard. They’ll have to feel that the service is reliable, secure and fast. And no matter how good Dropbox is at doing its job, it’ll have to deal with the fact that Internet access still has a tendency to conk out at inopportune times — a point the demo gods underlined by messing up the Wi-Fi during one crucial DBX demo. (It continued in the form of a pre-recorded video.)

Making the new features into something that people love even more than they love the current incarnation of Dropbox will be crucial; the company doesn’t plan to charge developers for the new capabilities it’s providing or the data it will be storing. Instead, it will continue to make money by charging its most loyal consumer and business customers for extra space, starting at $9.99 a month.

“Particularly when it’s new, people have to trust that it’ll actually work,” says Houston. Dropbox’s new role in managing data for all sorts of apps will be obvious — users will need to have a Dropbox account and be logged in for everything to work — but it can’t require too much attention. Referring to the company’s logo, Houston says that he wants users to think of Dropbox as “a little blue box that’s part of your phone, that’s part of a dozen apps on your phone, having it on Yahoo Mail and Facebook.”

“It’s a light switch,” he says. “I turn on Dropbox and expect it’ll work. It doesn’t have to be front and center at all times.”

I ended our chat by asking Houston how he uses Dropbox. “I’ve got my life in there — my photos, my personal stuff, my work stuff,” he answered. “Any time I have to collaborate, I have a countless number of shared folders. My work stuff, my band.”

“I’m probably not that different from an average user — I just have a lot of stuff.”