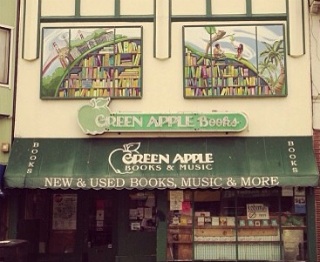

One of the many aisles of printed books at San Francisco's Green Apple

I am one lucky book lover. My local bookstore is Green Apple Books, a 46-year-old San Francisco institution located in the city’s Richmond neighborhood. It’s got 8,000 square feet spread across two storefronts, piled high with a wonderfully eclectic array of stuff: new books, used books, magazines, DVDs, CDs, vinyl LPs and more. I could probably spend a week there browsing full-time without getting bored.

Green Apple is unique, which is presumably one major reason why it’s very much with us in an era in which Borders is defunct and Barnes & Noble is in trouble. Still, I worry. I’m a fan of e-books and buy lots of them, but the more popular they get, the tougher it could get for independent purveyors of dead-tree tomes. And even before e-books came along, local bookstores were plenty challenged by competition from Amazon, whose deep discounts on printed books are impossible to match.

So when Pete Mulvihill, the store’s co-owner, asked me if I wanted to hear about its experiences selling Kobo e-readers and e-books for them, I jumped at the opportunity. I can’t claim any to be the epitome of journalistic detachment: I’m in favor of anything that helps Green Apple — and other great local bookstores like it — stay relevant and viable.

Headquarted in Toronto and owned by Japanese e-commerce behemoth Rakuten, Kobo doesn’t rival the high profile of Amazon’s Kindle and Barnes & Noble’s Nook in the U.S. But as a major e-book power that isn’t controlled by a giant book seller — with devices, apps and e-books to compete with the Kindle and Nook — it’s a logical ally for a local bookstore, which is why the American Bookseller Association partnered with it to help independent stores such as Green Apple delve into e-books.

Green Apple also participated in an earlier ABA digital initiative. That one involved giving local stores the ability to sell Google e-books through their websites, and it turned out to be a short-lived disappointment: Google decided to pull the plug after just 16 months.

The arrangement with Kobo, unlike the Google deal, gives Green Apple and other independents a line of e-readers they can sell in their stores. If someone buys an e-reader from the store, it gets half of the profit Kobo makes on the e-books that person buys. Bookstore customers can also register for a Kobo account through Green Apple, which gives the store a cut of all e-books they buy even if they read them on Kobo’s smartphone and tablet apps.

Barnes & Noble places Nook kiosks smack-dab inside its stores’ entrances where you have to avert your eyes to avoid them. Green Apple, however, isn’t applying hard-sell tactics to Kobo. The e-readers are one more item in a store that, while well-organized, is appealing in part because it’s so crowded and diverse that shopping feels like searching for hidden treasure. Almost by definition, they’re not the most interesting thing there: When people enter the store, Mulvihill says, “they probably wanted a print book or wanted to get away from a computer screen.”

And selling gadgets such as e-readers couldn’t be much more different from selling books, a profession that’s more likely to attract literary types than gearheads. Three or four of Green Apple’s employees are ready to answer customers’ Kobo questions, Mulvihill says, but “I have 20 staff members who won’t go near the thing.”

Even so, the Kobo initiative is important for Green Apple, and is an acknowledgment of a basic shift in the book business that it can’t fight. “I think of it as losing fewer customers,” Mulvihill explains.

So far, e-readers and e-books haven’t added up into a cash cow. Mulvihill describes the store’s profit on each Kobo device sold as “truly negligible” and says it might make $1 on a $10 e-book. “We’re used to selling a $10 book and making $4 or $4.50,” he says. And it’s not making up for the tight margin in volume: Since November 2012, the store has sold around 110 e-readers and collected commissions on 700 e-books.

That’s not nothing — Mulvihill says that there aren’t many individual printed books the store sells a hundred copies of in a year — but it’s also not enough to nudge its business model in a radically more digital direction. If Green Apple ever needs saving, Kobo and e-books are unlikely to come to the rescue.

The good news is that Green Apple isn’t endangered. Mulvihill says that the store’s sales increased by a percentage in the low double digits when San Francisco’s last Borders closed in 2011, and that it’s held on to most of that gain. It’s found Facebook and Twitter to be useful ways to keep in touch with loyal customers, and continues to tweak its product mix. (Vinyl has become a bigger business than new CDs.) And the store’s owners — four long-time employees who acquired it from its founder — are tending to tedious but vital matters such as finding ways to keep credit-card processing fees low.

“It takes a couple of hundred people coming through the door every day to keep the doors open,” Mulvihill says. “They keep coming in. We’re grateful.”

In other words, it’s still possible for a local bookseller to thrive in 2013 for much the same reasons that the best bookstores succeeded 20, 30 or 40 years ago. Mulvihill told me that this may be easier in San Francisco, which has a strong culture of neighborhood bookshops, than in most cities.

As much as I’d like to hear that Green Apple is making a killing in e-books, I’m relieved to know that there’s still a healthy business in just being Green Apple. Here’s hoping that it goes on doing exactly that for years to come.