Dr. Grace Hopper in her office in 1984, near the end of her U.S. Navy career

Yesterday, Google marked the 107th anniversary of the birth of the great computer scientist Grace Hopper (1906-1992) with a Google Doodle logo. The only shocking thing about that was the fact that Google had never paid Doodle tribute to her before: Nobody has ever been a more logical, deserving subject.

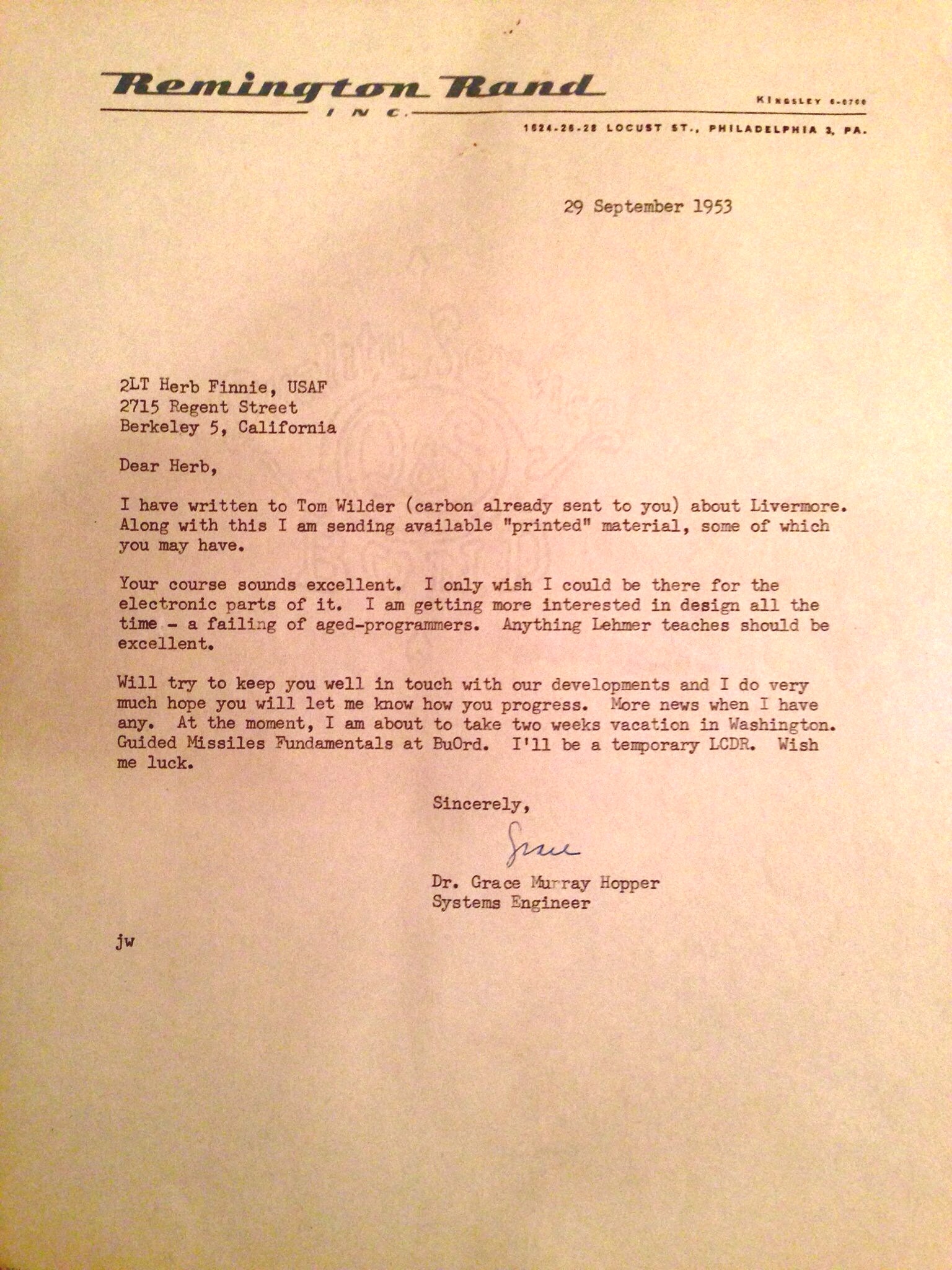

And Google’s celebration prompted my friend Ann Finnie to share something amazing on Facebook: a 1953 letter to her father from Hopper. Herb Finnie was a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force at the time.

Here it is:

Written when Hopper worked at Remington Rand — the company that produced the Univac I, the U.S.’s second commercial computer — the correspondence concerns a job recommendation Hopper had written on Herb’s behalf for a position at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory at Livermore, the predecessor of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

In retrospect, being recommended by Grace Hopper for a technical job is a testimonial of historic proportions. Even in 1953, when the computer industry was just getting going and Hopper was one of its architects, I’m sure that it was a big deal.

Hopper and Finnie had worked together on software for the Univac 1, and among the projects Finnie worked on using the Univac 1 (with serial number 1, no less): Hopper’s groundbreaking programming tools, a program that predicted the 1952 U.S. presidential election, and another that intentionally caused the computer to go haywire so that Air Force personnel could learn to troubleshoot it. (As Ann points out, that last program sounds like a proto-virus.)

Oh, and Herb, who was a native of San Marcos, Texas, taught Univac to play “The Yellow Rose of Texas.”

Later, Herb Finnie got a masters degree in mathematics from the University of California at Berkeley while still in the Air Force. He worked at the Pentagon and ended up spending 34 years as a systems engineer at defense contractor Lockheed.

I love everything about the letter: the fact it’s so obviously typed on a 1950s typewriter (presumably a Remington Rand model), the evocative Remington Rand logo, the old-timey format of the phone number and Hopper’s mention of a “carbon.” And, more than anything else, the fact that it shows such a legendary figure in such a human moment.

Her reference to “two weeks vacation” in Washington is a joke: Hopper, who joined the U.S. Navy’s WAVES during World War II and eventually became a rear admiral, was apparently going on some sort of special assignment for the Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance. So, I hope, is her description of herself as an aged programmer: She was 46 when she wrote this.

Ann found the letter in her late father’s foot locker while she was looking for something else. I’m so glad she did. And I’m sorry that the late-2013 equivalents of this sort of document are in the form of e-mail, which means that it’s highly unlikely that anybody will be able to enjoy rediscovering them in 2073.