Nolan Bushnell in 1986, with Atari's first game and a Macintosh computer

Once upon a time, back in the 1960s, there was a videogame called Spacewar!

It was remarkably ingenious and addictive, and probably would have become a pop-culture phenomenon if it weren’t for its one downside: You could only play it on a mainframe or minicomputer, at a cost of $120,000 and up.

For that reason, Spacewar!‘s fan base consisted largely of students who were lucky enough to have access to university computer centers. Oftentimes they indulged in the game in the wee hours, when nobody was around to chastise them for wasting precious computing resources.

Getty Images

One of those Spacewar! enthusiasts was a University of Utah engineering student and part-time amusement-park arcade manager named Nolan Bushnell. He thought that videogames could be a big deal. “The only question,” he remembers, “was how to bring them to everyone, not just those of us who could sneak into a computer lab late at night.”

In 1971, Bushnell and partner Ted Dabney managed to turn Spacewar! into the first mass-produced video arcade game, Computer Space. It wasn’t particularly successful. Undeterred, they continued their partnership, Syzygy, by founding Atari, Inc.. (Another company, it turned out, had first dibs on “Syzygy.”) They filed the incorporation papers on June 27, 1972, occupied 1,700 square feet of office space in Santa Clara, California, in the heart of Silicon Valley, and got ready to release a game they called Pong. The rest is videogame history.

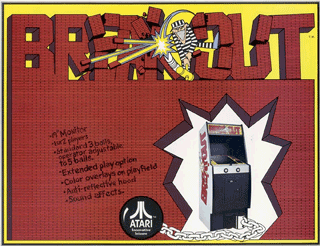

Like everyone else who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, I played them all: Pong, Breakout, Asteroids, Centipede, Millipede, Battlezone, Pole Position, Crystal Castles and my eternal favorite, Tempest. The first computer I bought with my own money was an Atari 400. So when I chatted with Bushnell this week to mark Atari’s 40th anniversary, I felt like I was talking with a man who helped invent my childhood.

Not that Bushnell invented all those games: Many, in fact, originated well after he left Atari in 1978, and all of the company’s home computers were released after his departure. As he was quick to tell me, he instigated Pong but it was entirely designed by another videogame legend, Al Alcorn. And Atari wasn’t responsible for bringing videogames into homes: The first game console was Magnavox’s Odyssey, created by Ralph Baer and also celebrating its 40th anniversary this year.

But Nolan Bushnell, more than anyone else, was the guy who turned videogames from a very impressive demo of very pricey technology into an enduring pop-culture phenomenon. Thanks to Atari, you didn’t need a mainframe to play the coolest games on earth. All you needed was a quarter.

(MORE ATARI: The Top 10 Atari Arcade Games)

At first, when Bushnell and Dabney were trying to turn Spacewar! into a commercial product, their plans involved trying to use Data General’s Nova, a minicomputer which started at a remarkably low $3,995. “The epiphany moment in the quest,” he explains, “was when I discovered that I could do these games without using a minicomputer.”

Curt Vendel

“I’ll bet I can do this whole game in hardware,” he remembers telling himself. He could, and did. It’s inaccurate to call Computer Space, Pong, Breakout and other early Atari arcade machines “computer games”–no computer was involved. Instead, they used dedicated chips and discrete logic. (Midway’s 1975 Gun Fight was the first arcade game to use a microprocessor.)

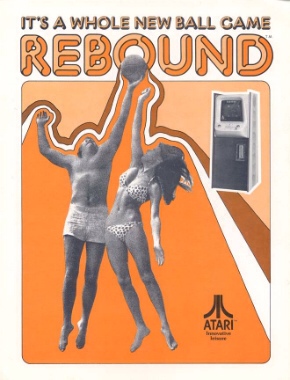

Videogames have gotten far more grandiose since the early days of Atari, but it’s not entirely clear whether they’ve gotten any more entertaining. Decades later, the industry is still milking the same concepts, except with fancier graphics and more levels. Atari produced shoot-em-ups, such as Destroyer. It did sports simulations, including Football and the volleyball game Rebound. It pioneered military games with titles such as Subs and Tank. “Our driving games were really, really good,” Bushnell says; examples included Le Mans and the first-person Night Driver.

AtariMuseum.com

During Atari’s peak years, it wasn’t just synonymous with videogames. It was the archetypal Silicon Valley success story, period. An entire category of tech-savvy politicians, such as vice-president-to-be Al Gore, were known as Atari Democrats. The company basked in Apple-like fame before Apple was famous.

And if it weren’t for Atari, there might not have been an Apple, at least in the form we know. Steve Jobs’ first real job after he dropped out of Reed College was at Atari; he worked there off and on from 1974 until he and Steve Wozniak started Apple in 1976. His time there was the closest thing he had to a business education, and Bushnell–an idea machine and a showman as much as a technologist–was a role model.

Tales of Steve Jobs’ Atari days are the stuff of legend. He was so difficult to get along with–and smelled so bad–that he was moved to the night shift. He was also assigned to engineer the game that became Breakout, which he outsourced to his friend Steve Wozniak–allegedly without cutting Woz in on most of the fee Atari paid him. (The Breakout that became a hit in arcades wasn’t based on Woz’s design.)

AtariMuseum.com

“You have to remember, we had a lot of imitators,” says Bushnell. “Creativity and innovation were the only weapons we had.” Consequently, he was willing to gamble on idiosyncratic people such as Jobs, who he calls “the ultimate passionate guy.” He says that Jobs brought a similar approach along with him when he and Woz started Apple, and that Apple reflects it to this day.

Atari was also a prototype for Apple and other Silicon Valley startups in another way: It boomed despite Bushnell’s youth, inexperience and lack of resources. He was 29 when he and Dabney started it, and his background consisted of his engineering degree, a stint as a journeyman employee at legendary Silicon Valley firm Ampex and the ill-fated Computer Space adventure. Legend has it that the founders’ initial investment was $500. (Dabney left Atari one year after its founding.)

“Atari showed that young people could start big companies,” Bushnell argues. “Without that example it would have been harder for Jobs and Bill Gates, and people who came after them, to do what they did.”

Strong National Museum of Play

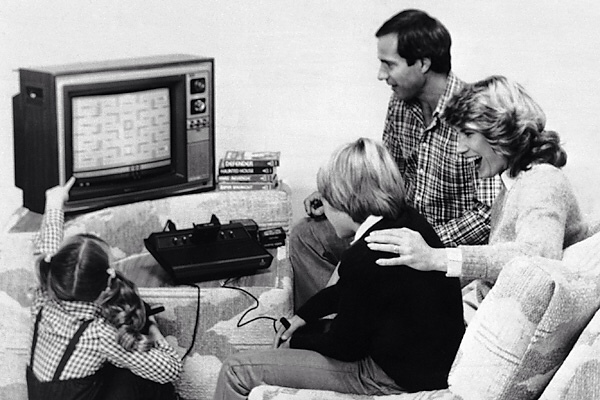

In 1975, Atari ventured beyond the arcade by introducing the first home version of Pong. Sears sold it for $98.95, or slightly less than 396 quarters. Two years later, it launched the Video Computer System (VCS), its first home system that took cartridges. Later and more familiarly known as the Atari 2600, it was an enormous undertaking.

It was so enormous, in fact, that paying for its research and development was a challenge, even when Atari sought outside investors. “Nobody perceived games to be a business,” Bushnell remembers, “so raising money was difficult.” In 1976, when the VCS was still in the works, he sold the company to Warner Communications for $28 million. (Much later, after divesting itself of Atari, Warner merged with Time Inc. and morphed into Time Warner, this website’s parent.)

By 1978, Bushnell and the Warner executives charged with presiding over Atari were clashing. In November of that year, Bushnell was forced out of the company he co-founded.

When I asked Bushnell if selling out to Warner had been a mistake, he sounded wistful and said that it probably had been.

Atari / AP

“Warner made a whole series of blunders which were not good for Atari,” he said. One example: “We were going to do this game network over telephone lines, but Warner couldn’t figure out why people would want to play games with people they couldn’t see.”

“If we had gone ahead and done it, it could have essentially been the Internet, in private hands. It’s kind of fun to think about owning the Internet.”

Atari may not have ended up owning the Internet, but for a while, it flourished without Bushnell. In 1982, it sold 12 million VCS units, made $2 billion in revenue and contributed half of Warner’s operating income.