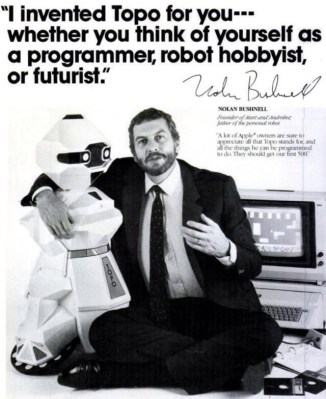

Nolan Bushnell in 1986, with Atari's first game and a Macintosh computer

But the company sat atop a videogame bubble that popped in 1983, in part because of a profusion of low-quality, poor-selling games–most famously the catastrophic E.T. In 1983, five years after Bushnell left, Atari crashed so hard that it looked like it might take the entire videogame industry with it.

(MORE ATARI: TIMEs 1983 article on the videogame crash)

Getty Images

Bushnell, meanwhile just kept going, Plenty of Silicon Valley types proudly label themselves as “serial entrepreneurs,” but few if any can match his record of coming up with ideas and turning them into companies–more than 20 of them to date, and counting.

Immediately after leaving Atari, he proved he wasn’t a one-hit wonder with Pizza Time Theatre, a concept that he originated at Warner and took with him. Like Atari, the kid-oriented restaurant chain with games (from Atari and others) and entertainment provided by Disneyland-style robotic animals eventually collapsed. But then, after merging with a rival, it rebounded. Today, without Bushnell’s involvement, it’s known as Chuck E. Cheese’s and has more than 500 locations.

None of Bushnell’s other companies have been another Atari or Chuck E. Cheese’s. Actually, they’ve tended to be short-lived, and some haven’t ever really gotten off the ground at all. But all of them have been interesting: Again and again, he’s formed or funded startups around big ideas that meld entertainment, information and technology in new ways, often latching onto trends long before most people even understood they existed.

InfoWorld

A few examples:

- Starting in 1983, ByVideo offered touch-screen electronic shopping systems that used videodiscs to display high-quality imagery of the merchandise.

- Androbot sold personal robots in the mid-1980s.

- Etak sold a navigation system for cars in 1985, before GPS existed; it used cassette tapes to store its maps.

- The same year, a talking stuffed toy named AG Bear provided Furby-like interactivity.

- In the early 1990s, Octus developed software for managing phone calls, voicemail and faxes on a PC.

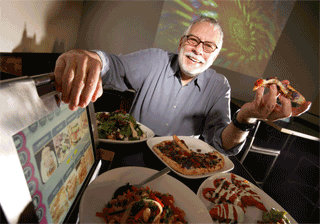

- In recent years, uWink operated a chain of restaurants with touch-screen computers at every table for ordering and playing social games.

Bushnell’s track record for trying things about 15 years before technology and the market are ready for them is so consistent that it makes me wonder if uWink-style interactive eateries might be everywhere by 2025 or thereabouts.

As for Atari, it survived its mid-1980s crash–just barely–and the pieces were picked up by Commodore founder Jack Tramiel. When his version of the company failed to make it into the modern era of videogames and PCs, the brand became part of Hasbro for a while.

Today’s Atari is a Paris-based game publisher, formerly known as Infogrames and before that as GT Interactive. It produces games for PCs, consoles and phones. Technically, it’s not the company that Bushnell cofounded in 1972. And yet it’s the first Atari since that one which he’s associated with: In 2010, he joined its board and agreed to serve as an advisor.

Reuters

Bushnell, who admits he never stopped caring about Atari, says it’s good to be back: “The brand is still powerful, and it’s not just a retro thing. It has a whole bunch of really important intellectual property, and a lot of people still think of Atari as a company of innovation.” (That said, a high percentage of the current titles published under the Atari imprimatur are remakes of Asteroids, Centipede, Breakout and other games from the first Bushnell era and the years immediately following it.)

In recent years, Bushnell has occasionally made the news by criticizing the current state of the industry he did as much as anyone to create. He’s not a fan of violent franchises such as Grand Theft Auto. “When I was running Atari,” he told me, “violence against humanoid figures was not allowed. We’d let you shoot at a tank…but we drew the line at shooting at people, with blood splattering everywhere.” (Death Race, a famous early arcade game which involved mowing down pedestrians, was the work of Atari rival Exidy.)

Still, as I chatted with Bushnell, I didn’t get the sense that he was a cranky old man fixated on past glories. When I asked him which of his accomplishments he was most proud of, he didn’t mention anything he’d actually accomplished yet. Instead, he excitedly pitched his latest startup, Brainrush, which is working on educational mini-games.

“It’ll dwarf the other stuff I’ve done,” he told me. “It makes learning five to ten times faster–kids love it.”

Brainrush’s goal, he said, is to “fundamentally change the way people learn and have everybody be smarter,” which will let “a whole bunch of really wonderful things happen.” It sounds…well, wildly ambitious even by Nolan Bushnell standards.

It was also an appropriate note on which to end our conversation. As much fun as it is to look back at what Nolan Bushnell was up to 40 years ago, it’s nice to know that the man who democratized videogames in the first place is still trying to figure out their future.

(Thanks to AtariMuseum.com’s Curt Vendel–the co-author of an upcoming 40th-anniversary history of Atari book–for the use of some of the images in this article.)