Microsoft's 1993 "Microsoft Mouse 2.0" -- supposedly equally pleasing in either hand, but with suspiciously right-handed curves

I’m not saying that Microsoft’s input-device designers never took the needs of lefties into account so much as that it was a losing battle.

Microsoft

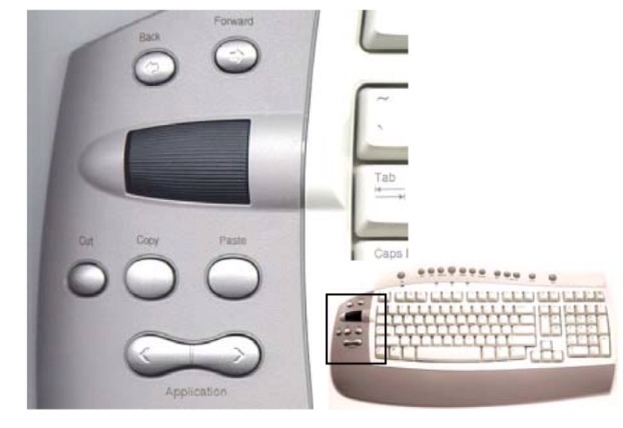

In this old research paper on the development of its Office Keyboard— which put a scroll wheel and special buttons on the left side of the keyboard, so you could use them while your right hand stayed on the mouse — the company said that 95% of all people moused with their right hand. That would mean that roughly fifty-percent of lefthanders were right-mousers, which sounds about right. With that in mind, there was no scenario under which it would have made sense to place the keyboard’s extra controls on the right side, which is where a left-mouser would want them.

In the same paper, Microsoft discussed a focus group it conducted while developing the keyboard. It included 12 righthanders, and one lefthander who moused with his right hand. Fair enough. Why bring a left-mouser into the process when his or her needs could never, ever supercede those of the right-mousing 95 percent?

Back in the 1990s, when the Microsoft Mouse 2.0 showed up on desks everywhere, it was an unhealthy influence on the input-device industry. Logitech, Microsoft’s mouse-making archrival, also started shaping mice to fit the right hand. Yet Logitech never deserted lefties entirely: It always offered some old-fashioned symmetrical models, and at some points offered models shaped specifically to fit the left hand. So in the mid-1990s, I tended to be a user of Logitech mice.

Microsoft

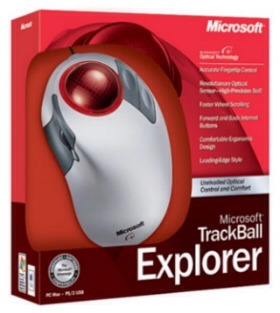

Then, at home, I switched to Kensington’s wonderful Expert Mouse — still available in a modern version — which wasn’t a mouse at all. It was a trackball, and the cool thing about trackballs is that they’re spherical, and therefore inherently well-suited to both right- and left-handed users.

Well, except for Microsoft trackballs: The company managed to invent one that could only be used with the right hand.

At work, I used a pricey left-handed, medium-sized Contour mouse prescribed to me by an ergonomic consultant hired by my employer. It looked a little like a medical instrument, and visitors tended to make fun of it, but I liked it.

Contour, incidentally, still makes left-handed mice. It only makes them in two sizes though, versus the three it once offered. Righties get four sizes, drat them.

I started out saying I didn’t intend to be whiny about the lot of the lefthander — and yet this article, so far, sounds pretty whiny even to me. Don’t worry: There’s a happy ending, and we’re almost there.

For a time, I fretted that as gadgets became more mobile, they’d grow even more right-biased. For example, the Tablet PC, which Microsoft thought would come to overshadow conventional laptops, replaced left-friendly QWERTY with handwriting recognition, which, if you’re left-handed, makes it tough to see what you’re doing.

Getty Images

And while I loved my PalmPilot, the Palm OS always felt like it was designed for right-handers: A lot of the features were over on the right edge of the screen, which meant that if you were tapping them with a stylus held in your left hand, you were covering the screen.

But the faster technology has progressed in recent years, the more it’s evolved in ways that eliminate the righty bias. Modern laptops, for starters, are kind to southpaws, in part because touchpads are as ambidextrous as input devices can get: They’re flat and rectangular, and the buttons, when they still exist, are at the bottom, not on one side. For this reason, it’s been years since I last used a mouse or trackball of any type.

Even many modern mice are more lefty-tolerant than most of the ones of the past. The trend has swung back to models which fit either hand equally well. And Razer, God bless it, even makes a left-handed gaming mouse — something I’m tempted to buy even though I rarely play games and never use a mouse.

For whatever reason, current technology products in general seem less obsessive about placing buttons and other controls on the right side, perhaps because so many of them are most often operated by remote controls. For decades, almost all TV sets placed their controls to the right of the screen. On my Toshiba, however, they’re on the left edge.

Heck, HP has even taking to selling what I think of as left-handed printers.

Most important, the arrival of the first iPhone in 2007 ushered in a new era of largely ambidextrous technology. Whether it’s intentional or a happy accident, the iPhone and iPad, and most of the gizmos that have drawn so much inspiration from them, are among the most lefthander-friendly gizmos in history.

Getty Images

On both the iPhone and the iPad, Apple’s iconic home button sits in the middle, not on the right side. In fact, while both devices do have nominal “right sides,” they use accelerometers to reorient themselves as you rotate them around; by design, they’re intended to be side-neutral in a way that PCs never are.

The only pointing devices you use are your own fingers and thumbs; either hand works equally well, and the displays are small enough that it’s not a hassle to reach any part of them with whatever digit you prefer.

For me, at least, handedness doesn’t seem to be as much of an issue with phones and tablets as it is with PCs and other devices. Sometimes I hold my phone or tablet in my left hand and operate it with my right hand; sometimes I hold it in my right hand and operate it with my left hand, Or I cradle it with both hands and use both thumbs, or in one hand and use the thumb of that hand. Any which way I try it, it works.

Having spent most of my life adjusting to a right-handed world — I now cut paper with my right hand and can’t even use left-handed scissors when I try — it’s a genuine thrill to think that technology is finally adjusting itself to me.